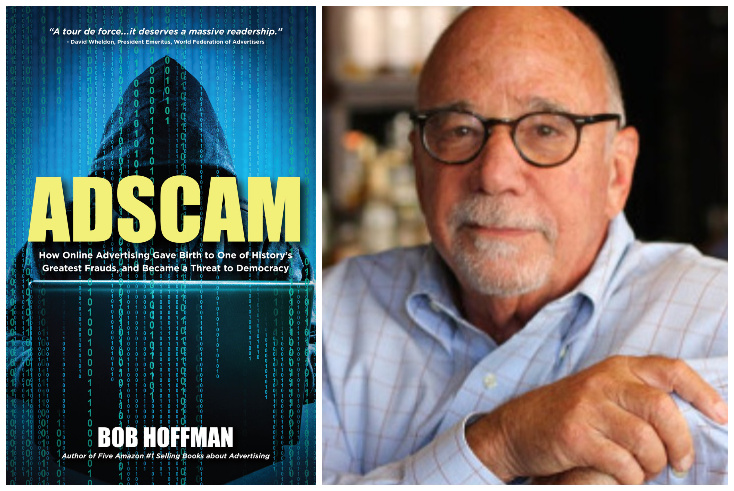

Why Big Tech scandals don’t shock us: reviewing ‘Adscam’ by Bob Hoffman

Review

In Adscam, author and ex-agency CEO Bob Hoffman walks a fine line between trying to grab the ad industry’s attention while offering harsh criticisms that few may want to hear.

Google is the subject bombshell report from Adalytics accused the Alphabet-company of violating its own standards for ad placements. According to the report, 80% of video ads Google’s video ad platform TrueView placed on third-party websites violated its own guidelines.

Google’s policies state that video ads will be played before sites’ main video content, and will be audible and skippable after five seconds. The service requires advertisers to pay for ads only when users watch 30 seconds of the ad, but the ad campaign analytics company found that potentially billions of dollars in ad spend was spent on “small, muted [or] auto-playing” ads. In some cases, no actual video content played between ads.

The report also accused Google of running ads on sites which did not meet its standard of “high quality Google Video Partners”. It identified cases on those sites in which the “skip” button on video ads was hidden or obscured to make it difficult for users to skip after five seconds.

In response, Google issued a blog post addressing the allegations. The tech behemoth said the report “used unreliable sampling and proxy methodologies and made extremely inaccurate claims about the Google Video Partner network.”

On LinkedIn, the reaction of author and ex-agency CEO Bob Hoffman to the news was particularly vitriolic. He writes: “Where are the feckless, useless ANA and 4As on the Google “Video Partners” scandal? Hiding under their desks, as usual? Aren’t they supposed to represent and protect advertisers?”

For the author of Ad Scam: How Online Advertising Gave Birth to One of History’s Greatest Frauds and Became a Threat to Democracy, this must feel like Groundhog Day. In the book, Hoffman reviews another shocking report published last year (also from Adalytics) in which Google was accused of placing ads on websites propagating Russian disinformation.

Setting aside Google’s alleged behaviour, Hoffman seeks to answer a wider question about the media and advertising industry’s apparently enlarged stomach for scandal. In Adscam, Hoffman offers an answer but it might not be one want to hear: the digital advertising industry, from top to bottom, is a racket. Gullible advertisers, directed by apathetic agencies, funnel billions of dollars into a programmatic supply-chain, most of which goes to unscrupulous adtech companies who cannot really trace where impressions are going, sanctified by snake-oil salesmen legacy ad fraud detection vendors who offer meaningless certifications, and abandoned by the very trade bodies meant to be protecting their interests.

But for Hoffman, the problem runs much deeper than advertisers sinking unspeakable sums of money. The mechanism which underpins the whole system – the tracking of users activities across the web through third-party cookies – has opened a Pandora’s Box of societal ills: political polarisation, targeted disinformation and harassment, and the funding of malign actors.

One shocking incident he mentions concerns the targeting of women seeking abortions. Last year, a report by Reveal and The Markup found that “Facebook is collecting ultra-sensitive personal data about abortion seekers and enabling antiabortion organizations to use that data as a tool to target and influence people online…”

As the Adalytics reports about Google shows, ads often end up running on low-quality websites using fraudulent methods to artificially boost impressions they receive. Hoffman cites multiple studies detailing the staggering rates of fraud in the US: Juniper Research estimated digital ad fraud in 2022 was worth over $60bn, the Association of National Advertisers in the US puts the figure somewhere between $81bn and $121bn.

For the UK, Hoffman cites the 2020 ISBA/PwC study of some of the UK’s largest advertisers (including Disney, Shell, Lloyds and PepsiCo) which found that ads bought programmatically wound up on over 40,000 different websites, over 80% of which were “not premium”. Hoffman jibes: “Not premium is a nice British way of saying crap.”

This way of putting things is typical of the acerbic writing style in Adscam. Hoffman is clearly having tremendous fun savaging ad tech companies and has no shortage of withering things to say about the industry’s trade bodies. Most times, we’re having fun reading it too.

To cite just one highlight: “Facebook’s VP of Integrity (yes, they actually have one) says they have undertaken “a long journey” to become ‘by far the most transparent platform on the internet’. Any time you see the word journey you know you’re in for some massive bullshit. (And, by the way, how do you become VP of Integrity at Facebook? I guess you train as VP of Diversity at the KKK.)”

But there are times where it grates a little or comes across as merely bitter. Hoffman rails against Mark Zuckerberg constantly throughout the book, at one point quoting him and declaring that his words are the “pronouncements of an infantile narcissist.” And, while it is very funny to refer to representatives of tech giants as “spokesquids”, these moments can feel like a distraction from the genuinely important message of Adscam.

Another thing on the subject of style: don’t come into Adscam expecting to read essays full of gorgeous, ornate prose. The book is basically a thematically-ordered series of articles Hoffman has written over the years, and some chapters are literally just sets of bullet points that run over several pages. This can be disappointing at times as his more worked out and structured essays are genuinely a pleasure to read.

But, despite this, Adscam is indispensable. There were moments where I felt like Hoffman was physically shaking me and shouting: “Why are you acing like this is normal? This shouldn’t be normal!”

A good example is when he’s laying out the raw data on how much real-time-bidding (RTB) technology broadcasts our personal data across the web. He writes: “The average person in the US has their online activity and location broadcast to thousands of companies 747 times every day. In Europe, RTB transmits an average person’s data 376 times a day.

“It has been reported that by the time an average child is thirteen years old, the adtech industry has 72,000,000 data points on that child.”

That figure feels obscene and should give all of us pause. Indeed, as the book progresses and these galling facts pile up, Hoffman’s insistence on calling the current model ‘surveillance advertising’ feels less hyperbolic and more like a sober acknowledgment of the situation.

So what is to be done? In the speech which helped jump-start his political career, Ronald Reagan said of the Democrats: “They say we offer simple answers to complex problems. Well, perhaps there is a simple answer — not an easy answer — but simple.” So, Hoffman has his own simple-but-not-easy answer (which unlike Reagan doesn’t include supporting genocidal governments in Central America). He wants us to ban tracking — completely. While he doesn’t believe that it will solve all digital advertising’s problems, he does thinks it’s necessary to make any progress all.

Personally, after finishing Adscam, I felt a deep sense of relief that Google plans to get rid of cookies next year. It remains to be seen whether its cookie-alternative really is a privacy first solution (and Topics API certainly does retain an element of tracking) but it feels like a step in the right direction.

The digital advertising landscape may look unrecognisable after the removal of cookies but Adscam is still a vital read for marketers. Even if it’s to consider what’s at stake beyond the bottom line.