Can joint industry collaboration save us from ecosystem collapse when the market gets it wrong?

Opinion

What should we learn from the Dust Bowl-era migration of farmers in 1930s America? You can only reap what you sow, says Tony Regan.

There are signs that the complex digital ecosystem we’ve built is more fragile than resilient. With most media investment now paying for outcomes from platforms not measured by independent industry currencies, media measurement has become privatised, and we need industry-level collaboration to safeguard our collective future.

Barb’s Caroline Baxter recently reminded us of the importance of maintaining balance in the TV ecosystem and of trusted, independent evidence as our industry’s version of the ‘sunlight…that keeps everything alive and in balance’.

In my role as consultant to the IPA and all the UK joint industry bodies, I’ve been thinking about audience measurement and the urgent task that’s facing the industry to avoid our equivalent of what climate experts describe as ecosystem collapse.

Over 20 years, our industry has created an increasingly complex trading ecosystem, often celebrating our inventiveness during a time of profound transformation. But the reality of the ecosystem we’ve built is that it’s full of adaptations that signal its fragility rather than its vigorous interdependence.

Layers of tech innovation are devoted to patching up the various ways the system falls short – on viewability, fraud, non-human traffic, brand safety, or looking to address weaknesses or variability in the amount or quality of attention, and adding provisions for brand suitability. We’ve been busy inventing antibiotics, but maybe they’re just not strong enough.

There’s a lesson from history: millions of people lost out badly when a crucial ecosystem collapsed.

This picture is from the 1930s USA – specifically an area known as the Great Plains, a vast expanse of 100 million acres of grassland across five US states. The region faced a disaster that made it better known as the Dust Bowl.

From the 1860s onward, this land of opportunity was settled by farmers who ploughed grassland prairies to grow wheat. Demand increased further after the First World War.

When the price of wheat crashed during the 1929 stock market collapse, farmers needed to grow more, adopting more intensive farming methods that damaged the soil: overgrazing, over-cultivating, and clearing grassland and trees that protected their environment. Their tech was mechanisation – tractors and combine harvesters in the name of efficiency. Little did they know what was coming.

This had always been a windy landscape, but when drought conditions came in the early 1930s, the soil literally blew away. There are songs about it. Here you can see what happened when soil from one area was lifted into a dustcloud that then fell like a blizzard of snow and engulfed another farm.

From Montana in the North to Texas in the South, a green and fertile landscape became a desert. The land was suddenly barren. During the 1930s, the largest migration in US history occurred, with an estimated 3.5 million farmers and their families abandoning their homes and livelihoods to seek work elsewhere. It’s deep in the mythology of many American novels and movies.

What’s that got to do with us?

Advertising both builds demand and harvests demand. And there are many effectiveness experts who remind us that you can only reap what you sow.

Les Binet repeatedly warns: “Marketing is becoming more efficient but less effective.” At this year’s IPA Effectiveness conference, his message was “Go Big or Go Home,” with reach rather than targeting as the best route to effectiveness.

Or here’s Laurence Green, leading effectiveness at the IPA:

All the evidence is that long-term brand-building investment remains the path to sustainable, profitable growth and returns. If all you’re doing is harvesting current demand, you’re going to run out of road pretty quickly. Priming future demand is the key”

Or Graeme Douglas, founding CSO at Bicycle, reminding us in various posts on LinkedIn that advertising’s job is to create memories, mental availability and brand preference:

We don’t need more targeting. We need more memory. Think of the Cadbury Gorilla. You didn’t remember it because it was targeted at you. You remembered it because everyone saw it, talked about it, couldn’t escape it.”

Media agency comms planners and strategists might just be the sustainable farmers we need. Whilst media spend has been flooding into tech platforms, they’ve been filling their weighed-down bookshelves with cutting-edge scientific evidence that just wasn’t available 10 or 20 years ago.

Evidence about how advertising actually works: from neuroscience, behavioural economics, psychology, attention – pointing to the importance of fame, emotion, creativity, and reach.

Independent evidence on reach should be in high demand to enable modellers to fully explain how advertising drives business outcomes. By knowing how many people have seen or heard or come across an ad, how often and for how long. By linking levels of exposure to effectiveness. By enabling share-of-voice calculations to inform investment levels sufficient to grow market share. It’s a proven formula.

Signals in the noise follow-up

With support from the IPA, which represents the agencies on all JIC boards, the JIC bodies are collaborating to highlight the unique value of joint industry data in an outcomes world. Data that’s independent, objective, transparent and accountable. Data that’s the product of cross-industry collaboration, buy-side and sell-side, guided by principles that all parties agree on.

Together, they published a 2023 report titled Signals in the Noise, and in early 2026, they’ll release a follow-up report focused on evaluating the effectiveness and the power of joint industry exposure data in building the full picture of how advertising delivers outcomes.

It’s necessary because JIC data now seems less relevant to an industry sold on the promise of outcomes delivered by companies pushing proprietary data rather than independent evidence that has undergone joint industry scrutiny.

Are these platforms the equivalent of the salesmen selling shiny new combine harvesters and tractors to Dust Bowl farmers, for ploughing up the grass in every distant corner of their homesteads, putting the whole landscape at risk?

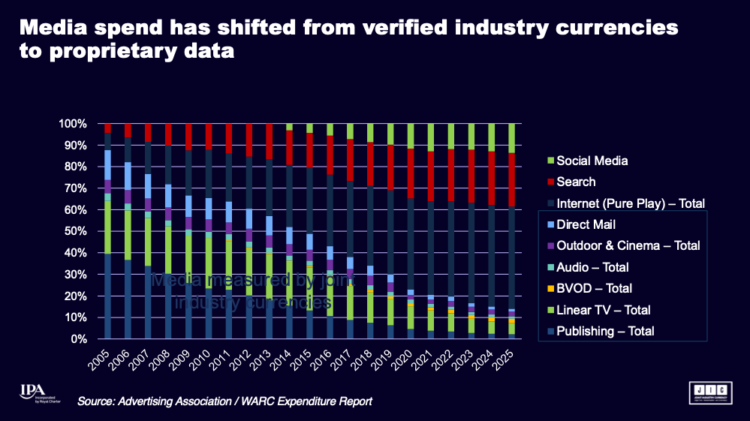

This slide, based on UK media spend data, shows the 20-year shift in the percentage of total spend covered by the joint industry currencies.

Back in 2005, things were starting to change as digital platforms began monetising through ads, but before that, industry currencies had been the only way for the buy side and the sell side across all media to do business with each other.

Fast forward to today, and perhaps 80% of the money flowing from buy side to sell side is not traded via JICs, but rather to buy outcomes.

You could interpret this simply as digital transformation sweeping away antiquated ways. Creative destruction. A simple battle between two media philosophies – reach vs outcomes.

You might see yourself on one side or the other of that divide – accustomed, as we’re now, to seeing everything through a lens of winners and losers. It’s OK, I’m part of the future, I’m in the outcomes business, we’re winning.

My appeal today is for the industry to see beyond winners and losers and instead work together to ensure our ecosystem is sustainable. It might not be vigorous, innovative, or a sign of things to come. It might instead be fragile, damaged and vulnerable to collapse.

The joint industry currencies originated from a collaboration between the buy-side and the sell-side to create value for all. They have a decades-long history but don’t stand against change – they themselves are constantly innovating to recognise and adapt to new audience behaviours.

It’s time for the two sides of the industry to collaborate again – brand and performance; demand growers and harvesters. It may also be time to work together to ensure that joint industry principles are adopted more widely, beyond the commissioning and oversight of audience currencies for established media, and to provide standards that support a more transparent and healthier ecosystem.

The story of the Dust Bowl is one in which everyone chose to let the market decide. After the disaster, massive land-restoration programmes led by the Roosevelt administration made the landscape viable and productive for farming again. A collective endeavour was required to repair the damage caused by the over-exploitation of a limited resource.

Our industry desperately needs to rediscover its spirit of collaboration and the value of shared industry principles – perhaps the only way to avert our own dustbowl disaster and secure a healthy ad ecosystem for the future.

Tony Regan is a partner at Work Research and a consultant for the IPA

Tony Regan is a partner at Work Research and a consultant for the IPA