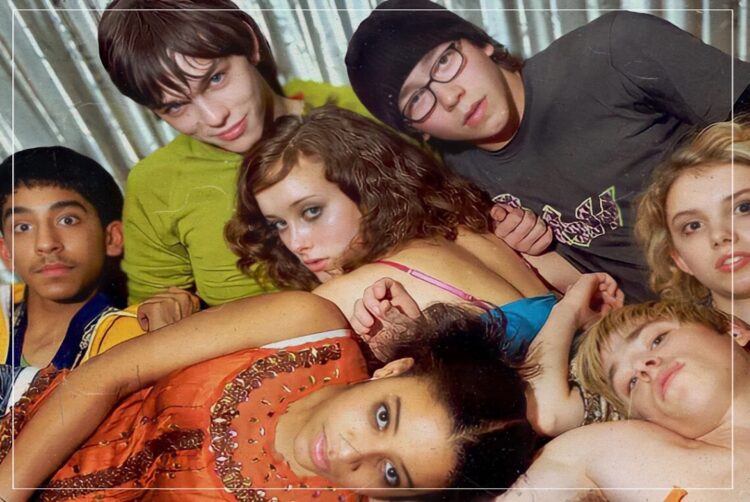

The original Skins shows broadcasters a lesson relevant for today

Opinion

Entertainment marketing should return to a more patient approach: bespoke content experiences designed for specific places, scenes, and sensibilities, says James Kirkham.

When my agency, Holler, handled the marketing for the E4 series Skins in 2007, the context mattered.

Television still had some gravity. And to an extent, young audiences still gathered around the broadcast moment – as long as they knew enough about the show in advance so that they could taste it, feel it and experience it enough prior to indulging together.

But something was shifting fast, and Channel 4, to its credit, leaned into the edges. It allowed a group of slightly feral internet people to treat the show not just as a broadcast asset but as a cultural object that needed to be discovered in the wild.

The work didn’t begin on social platforms, as people often misremember. Instead, it began in fashion spaces, music scenes, art and design blogs, youth forums, nights out, magazines, and micro-communities.

We created bespoke content for those places that was native in tone and rhythm. So, not trailers sprayed everywhere but fragments that felt like they’d emerged from the culture itself.

Those audiences were then gently drawn together and allowed to collide on MySpace, where conversation, creativity and participation took over.

Social media was the consequence, not the strategy

Over time, that thinking was flattened into a single lesson: ‘be on social’. Meanwhile, those platforms multiplied, and their algorithmically driven, highly monetised feeds accelerated. And the vanity metrics took hold.

So, marketing became an exercise in asset distribution rather than audience cultivation. Instead of many doors leading into a shared room, everything was forced through a single narrow corridor.

Now, almost two decades later, broadcasters are under genuine existential pressure.

Netflix has not only redefined scale and taste, but it’s also moving confidently into live events and cultural moments.

Meanwhile, traditional terrestrial broadcasters are finding that social no longer behaves as a dependable amplifier for audiences that are so fatigued that their reach is brittle and engagement is thin.

People care less, trust less, scroll past more.

So, in 2026, the irony is that the original lesson of Skins is suddenly useful again.

The future of entertainment marketing isn’t about shouting louder on fewer platforms but about returning to something more patient: bespoke content experiences designed for specific places, scenes and sensibilities.

Mining audiences pool by pool – fashion kids here and music obsessives there and a sports crossover somewhere else – but with each treated with respect, language and craft that feels native rather than imposed.

The broadcaster’s job is to create multiple points of entry and design the moment when those audiences meet. This is where 2026 gets interesting.

Forget using AI to automate trailers or endlessly version key art, which is a dead end.

Instead, find real opportunity in the moment of convergence – the point where all those carefully gathered audiences meet in a shared space, where AI can act as a kind of cultural conductor.

AI can surface patterns of interest, map affinities between groups, suggest unexpected collisions, and create adaptive experiences that respond to who is present rather than broadcasting blindly at everyone.

Think less algorithmic feed, more intelligent common space – somewhere a fashion-led audience can discover a music-driven interpretation of a show, or where younger viewers encounter older cultural references without being patronised.

A space where participation doesn’t mean comments under a post, but contribution to a living, evolving world. Where AI’s role is not to replace creativity but to help orchestrate coexistence at scale.

Broadcasters once understood this instinctively. They knew how to fish in different waters, then build the lake. But somewhere along the way, the lake became all that mattered, and the fishing stopped.

If broadcasters want to survive the next decade, they need to remember that they are not platform operators competing with Silicon Valley.

Instead, they are cultural hosts. Their advantage is not distribution efficiency but the ability to create environments where different audiences can gather, mix, and stay a while.

Skins worked because it respected its audience’s intelligence and plurality.

Yes, over the years, tools have changed, and the stakes have risen. But even so, the principle has remained quietly vital – and still is.

Going to people where they already are and speaking in ways that belong is the only way to build something worth coming together for. That’s not TV nostalgia from a golden age; that’s unfinished business.

James Kirkham is the founder of ICONIC

James Kirkham is the founder of ICONIC