Media strategists need to plan for distraction and use visual and auditory attention together.

Today’s Thinkbox event, Earning Attention: vision and sound in advertising, heard an introduction by Dr Polly Dalton, professor of psychology at Royal Holloway, who told delegates it was important to remember attention was multisensory and not “an all or nothing process” where one thing or another gains 100% attention.

She defined attention, in every day usage, as “an incredibly complex and multifaceted ability to do a type of prioritisation” and said in academic literature it was often divided into specific functions of vigilant or selective attention.

Vigilant attention is the ability to stay engaged with a task, which might be repetitive over time, but still be able to respond when something unexpected happens. Selective attention is linked to the ability in the moment to prioritise or deprioritise some aspects of our environment around us.

She gave a demonstration of selective attention asking attendees to listen to a short clip of a busy scene and focus only on the female voices. Afterwards, she asked the audience if they had heard the man in the middle of the clip repeating “I’m a gorilla”, and only about 30% of the audience raised their hands.

Dalton added it was important to “balance” attention and think about the “nuance” which was expanded upon by Dr Ali Goode in a new study he presented to attendees on visual and auditory attention in TV ads, and the impact of distractions on memory.

Industry must not tie itself ‘in knots’ over attention

Audio most important when people are distracted

This academic study built on a whitepaper last year on attention and TV advertising, Thinkbox’s Second Life, and another study with ITV Goode carried out in 2012.

He set out to find out how important audio was for attention, how much attention was “left over” for ad processing when people were doing something else, do eyes and ears work independently and are ads better when they are multisensory.

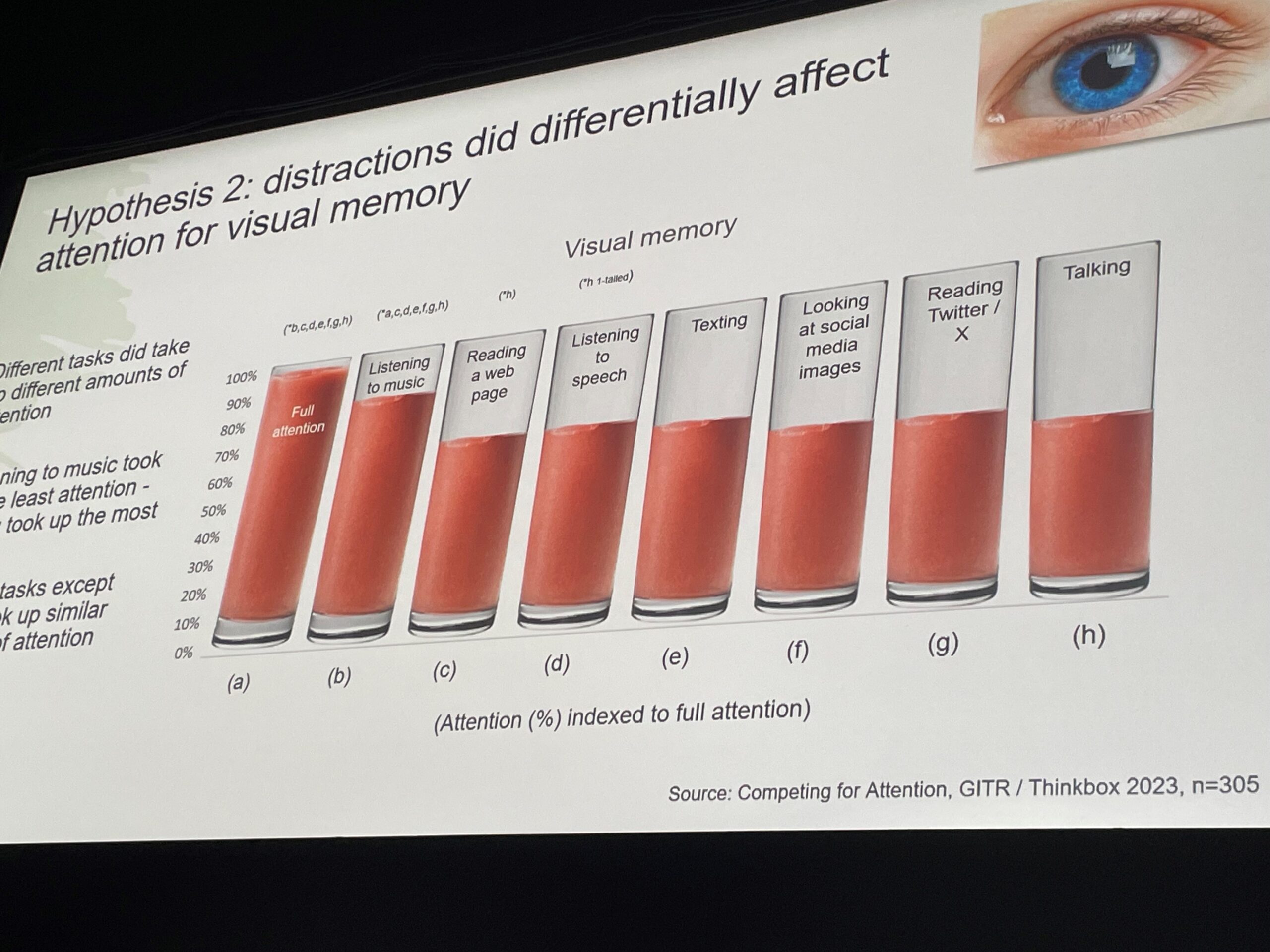

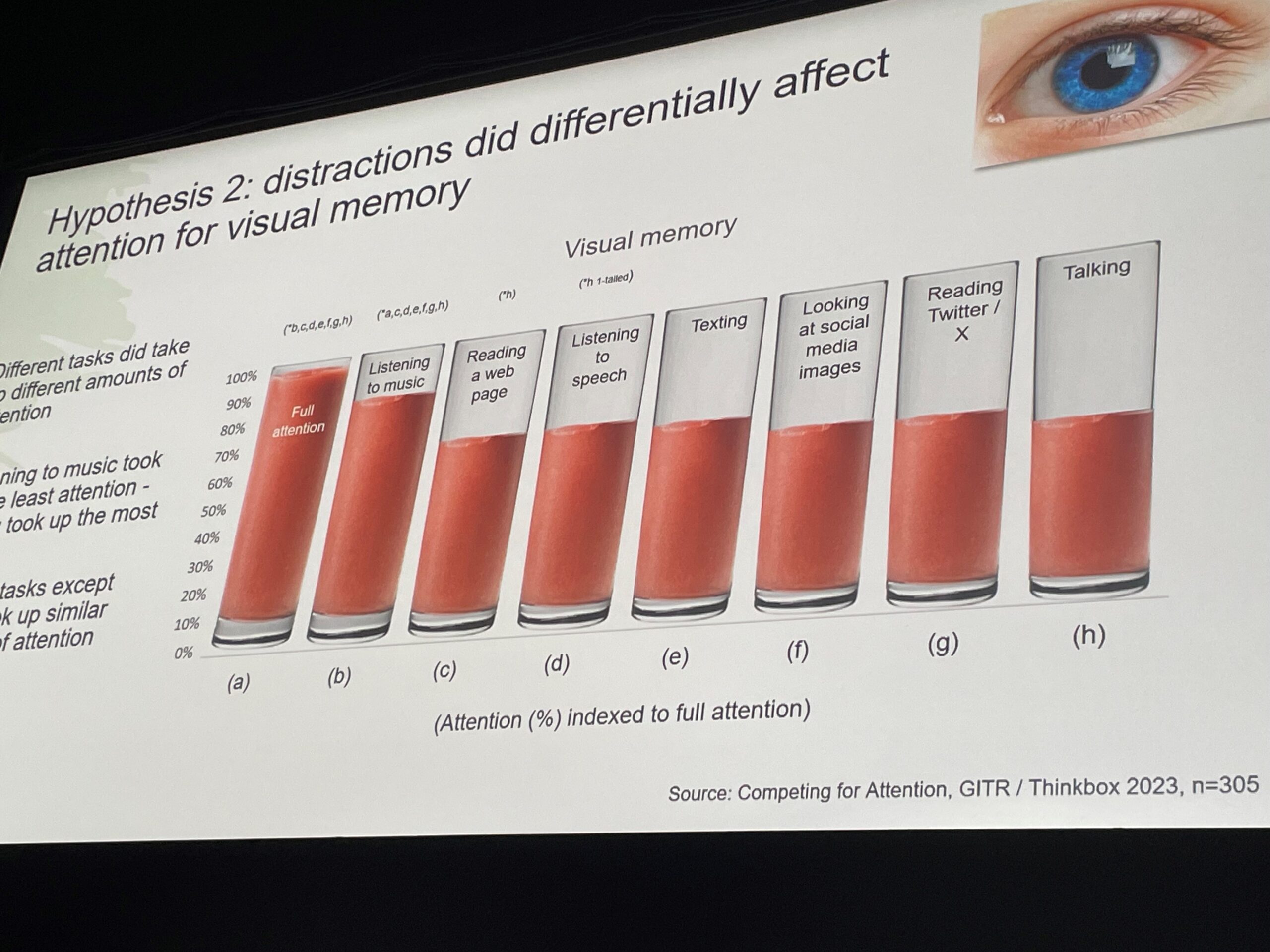

Goode used a sample of 305 people and compared their visual and auditory attention to and memory of a series of ads while doing seven different “distractions” or tasks common while watching TV including; listening to music, reading a web page, listening to someone talking, texting, looking at social media images, reading Twitter/X and talking to someone.

The attention to the ads while doing these tasks was indexed against full attention levels and found that auditory retention was “significantly higher” meaning when people were distracted they were more likely to recall, retrieve and encode what they’d heard rather than what they saw.

Auditory attention was particularly important when people find attention between tasks and in this state people can continue to understand spoken message, phrases, sonic cues (like McDonald’s whistle), music driving the creative and jingles.

Goode said: “One of the key things to think about was that the split between our eyes and ears is that we do not look around for stuff to listen to, our ears tell us where to go.”

Another finding was that while different distractions affected visual and auditory differently. The attentional load of doing different tasks affected the amount of attention available for visual processing of an ad, but there were still “plenty left” for auditory attention with the lowest scoring tasks registering 60% against full attention.

The study also discovered visual and auditory distractions interrupted both visual and auditory attention, so hearing something interrupted visual attention and looking at something interrupted auditory attention, rather than visual or auditory distractions only affecting visual or auditory attention respectively.

In addition, ads included in the survey that “carried meaning” in both visual and auditory got more responses than auditory alone, so they were “better” when they are multisensory. This led Goode to say that if you were not using audio and maximising its benefit, you were “missing out”.

He explained: “You’re missing out on the fact that when people are distracted, audio is going to be more resilient to that distraction. When people are distracted, it can communicate and it can manage visual attention as well and get eyes on to the screen.”

However, he stressed the importance of attentional load and making sure you could use people’s “leftover” attentional load efficiently.

We have to plan for distraction

Later on Goode showed the audience a Virtual Reality Media Room on screen which he used in other research to show attention to TV ads with multiple distractions including incoming texts, Alexa reminders, and news alerts.

On a panel immediately after, Geoff de Burca, joint chief strategy officer at EssenceMediacom, said: “The biggest single thing to me is the importance of getting creative. You can watch those rooms and it just shows how different the way the adverts are consumed to the way they are created. We’re sitting in rooms with clients, we’re studying ads in a very focused, concentrated way, but of course, they’re being viewed in a distracted way, and so planning for that distraction, and actually actively thinking about it in every conversation, assuming that the communication we are putting out probably will be consumed in a distracted way.”

Mark Barber, planning director at Radiocentre, made the case for consistency of audio messaging being most effective, as well as leveraging mood and need states to get the highest recall. He cited a study Radiocentre had conducted with participants doing other tasks while the radio was on in the background.

Dr Polly Dalton echoed this as they made points about relevant context contributing to someone’s attention in a multisensory world.

Adwanted UK are the audio experts at the centre of audio trading, distribution, and analytics. We operate J‑ET - the UK’s trading and accountability system for both linear and digital radio. We also created Audiotrack, the country’s premier commercial audio distribution platform, and AudioLab, the single-point, multi‑platform digital audio reporting solution delivering real‑time insight.

To scale up your audio strategy,

contact us today.