The Fiver: futility, bottom-right syndrome and more

This week it’s back to the Fiver format for Dominic Mills, featuring insight and comment on things that have caught his eye

#1. Futility, part 1

Let’s start with with news of a rap across the knuckles from the ASA for Hollyoaks star Jennifer Metcalfe, aka Mercedes McQueen. Wearing her influencer hat, Metcalfe was hired by hair brand, Haircybele to promote a discount offer (pictured above).

Only she neglected to mention on her Instagram post, via the appropriate label (ie #ad), that this was a commercial communication. Cue a finding against her.

So far, so (sort of) normal. Hats off to the ASA for all the hard work it does on trying to bring a semblance of control to the Wild West of influencer marketing, but this must feel to the ASA like it’s playing King Canute. It will always be batting against the tide.

Consider it, for a moment from Metcalfe’s point of view.

She’s no doubt busy, an offer of easy money comes in, and why should she be arsed to go through all the bother of labelling a post, or indeed understanding why it’s necessary? Even if she did, there’s no sanction against her and no reason she won’t get work from other brands.

Futility indeed.

Plus, there’s two other elements to the story that make me laugh.

First, reading its report, it’s clear the ASA is deeply miffed that Metcalfe completely ignored its investigation into the promotion. “The ASA was concerned by [Metcalfe’s] lack of response and apparent disregard for the code. We reminded her of her responsibility to respond promptly to our enquiries in future and told her to do so in the future.”

That’s telling her! It’s like Alok Sharma writing to Kim Jong Un to complain that North Korea needs to step up its game for COP26 and getting antsy because he hasn’t had a response.

Second, as the ASA report notes, Haircybele had no mechanism for tracking the effectiveness of the promotion, whether by actual sales or click throughs.

So what was the point? Madness and perhaps more futility.

#2. Bottom-right syndrome

If you’re reading a press profile with a celeb or quasi-celeb and it’s not immediately clear why they’ve got all those column inches, it’s worth going immediately to the bottom-right corner of the piece.

There you will usually find a small italics paragraph indicating that celeb x appears courtesy of brand y or is an ambassador for brand z. You can then decide whether it’s worth continuing or perhaps saving yourself a couple of minutes.

I’m making this up, but it might be something like this: ‘Bear Grylls is a global brand and mental health ambassador for Cotswold Outdoors and has just designed a new range of extreme hiking socks, available now’.

At this point you may decide not to continue.

I just don’t understand why the press colludes in this sort of thing, or indeed the celebs.

They both come out looking completely powerless, in hock to some brand no-one gives a stuff about, and which is of no relevance whatsoever to the story.

And so it was that the Sunday Times magazine two weeks ago featured one-time gossip blogger Perez Hilton where, bottom-right, was a credit for My True 10 CBD Gummies.

Come on. How low has the Sunday Times fallen, or how lacking in self-confidence is it that it has to trade an interview for a mention of a CBD gummy (which, it turns out, is a new line of business for Hilton?

Still, the paper probably felt it stood up for itself by making zero mention of the gummies. Small victory.

So, if we think of this in the context of the Metcalfe/ASA story, we might ask why this sort of practice, which is not materially different to the activities of an influencer, escapes the scrutiny of the ASA.

I suspect the only way to find out is to make a complaint….uuurrgh.

#3. Born online, born for telly

Two stories in the business pages caught my eye this week.

One, Cazoo registered a 500% increase in used-car sales volumes from Jan-July this year (4,084 to 20,000+).

And two, following a new round of investors buying in, Octopus Energy — one of a handful of new-generation electricity suppliers still standing, it seems — is now valued at $4.6bn.

Both are what you might call businesses born online (Octopus in 2016, Cazoo in 2018), lacking bricks-and-mortar presence and reliant, in different ways, on technology.

Plus, both are big TV advertisers, and since their TV spend shows no sign of slowing, it’s probably safe to conclude that their rapid growth is a consequence.

Cazoo, for example, is part of a group (Cinch, Webuyanycar etc) whose spend has increased by 235% over that period.

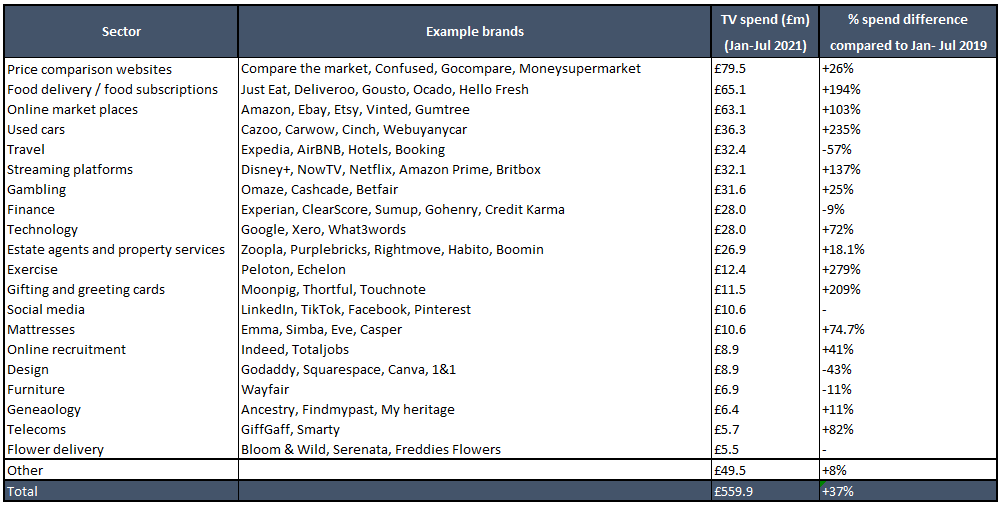

However, the interesting thing is that they’re part of a much wider phenomenon, as identified this week by some Thinkbox analysis, which shows that spend by this cohort hit £560m Jan-July this year, 37% up on the same period in 2019 and accounting for 20% of all linear TV spend.

Obviously, since ‘born online’ is a sort of meta-category, it is less of a surprise that it is now bigger than food (10%), finance and entertainment.

I’ve touched on this before but Thinkbox identifies a clutch of reasons for this: the presence of category disruptors driving fierce competition, the pandemic-driven shift to e/m-commerce and, underpinning it all, a VC-driven business model that prioritises rapid growth — all boxes TV ticks.

I started off this item thinking that what Thinkbox and its members really needed to ram home the point was for one of these advertisers — JustEat, Airbnb, Moonpig or Etsy, for example, — to win an Effectiveness award (2022, when the next set run).

But that’s not the case really. If they keep spending, the aim of their business model — world domination! — means it’s working. If they don’t, chances are they’ve failed.

#4. Futility, part 2 (of the academic kind)

A couple of weeks ago, measurement geeks and, no doubt, a few marketers gathered virtually for the US Advertising Research Foundation’s annual get-together.

FMCG players, I’m sure, were particularly excited by one of the presentations. This was from Professor Anna Tuchman under the beguiling title ‘TV Advertising Effectiveness and Profitability: Generalizable Results from 288 Brands’. Here’s a link.

Phew. Exhaustive or what?

Who wouldn’t want to get their nose under that particular bonnet (or hood, to stick to American-ese). Better (or worse), the study promised to reveal that TV produced “negative ROIs at the margin for more than 80% of brands”, implying over-investment in advertising for most firms.

[advert position=”left”]

Only what the conference blurb neglected to say, as indeed does the paper until several pages in, was that the study covered the period 2010-2014.

FFS! What on earth is the point of that?

My thanks to GroupM’s Brian Wieser’s excellent weekly blog for pointing this out.

Somewhat kindly, before listing about 20 caveats, he notes that 2010-2014 was a period that “probably feels a lot different today”. Yeah, like the Iron Age does.

Still, no doubt all the effort that went into the paper helped with securing academic tenure, even if it is of zero use to anyone else.

#5. Perceptions of value

It’s that time of the year when brand valuations rain down thick and fast.

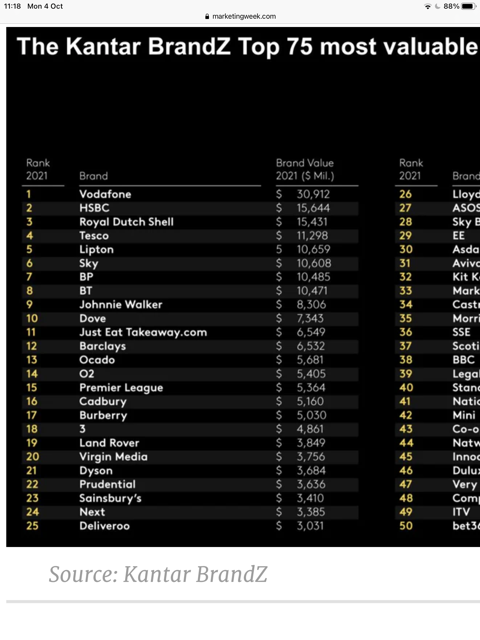

The Interbrand study comes out in a couple of weeks, but it was beaten to the punch last week by Kantar’s BrandZ report.

Looking at analysis of the UK results, there’s some interesting stuff about a bounce back in collective valuations post-pandemic and rapid growth among brands like Royal Mail, Sainsbury’s, ASOS and two gambling operators (Sky Bet and William Hill), which tells us something about the shifting sands of the economy.

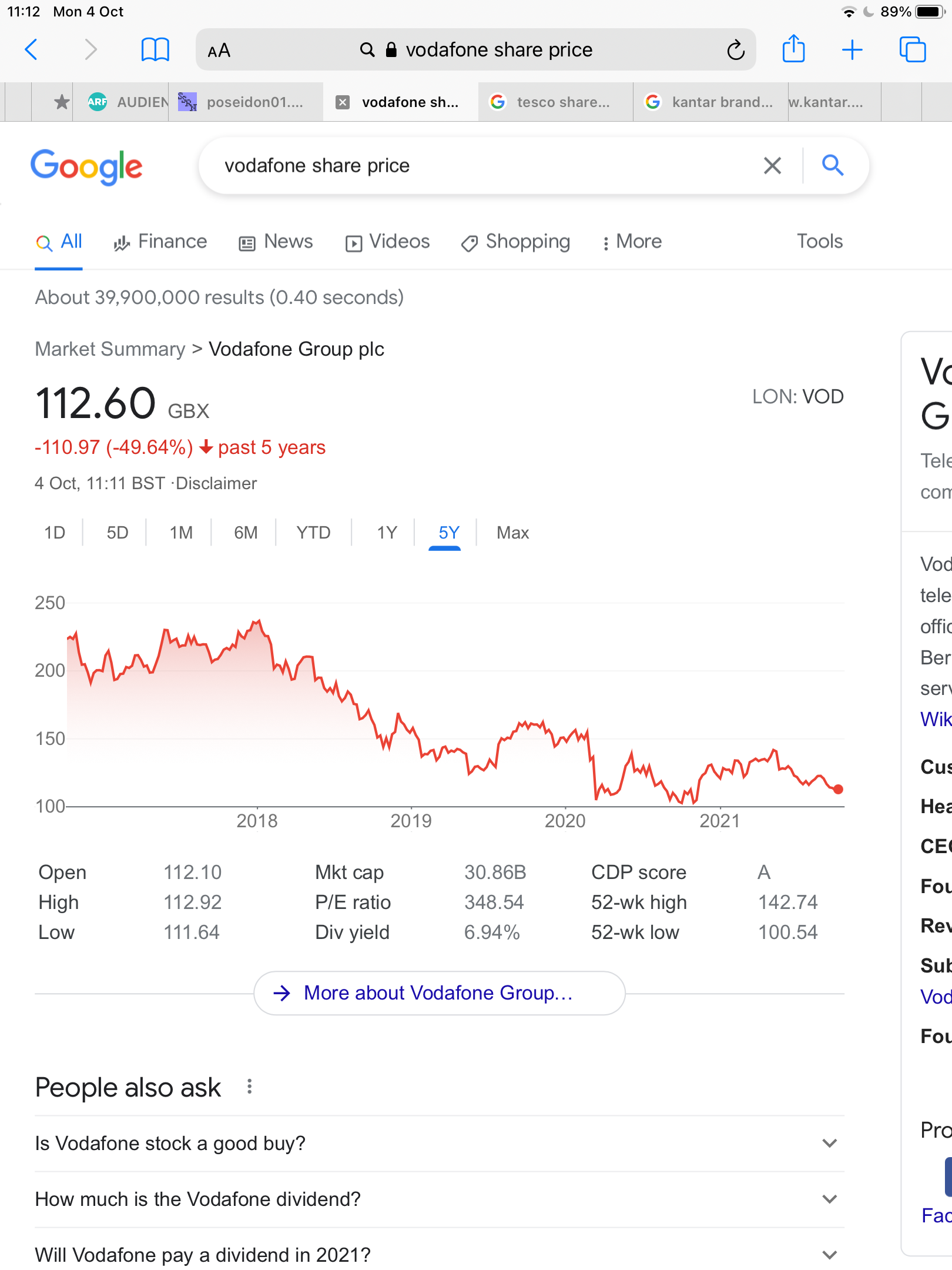

But there’s one thing that strikes me as odd. For the fourth year running, the UK’s most valuable brand is Vodafone. At $30bn, it’s up from last year, and marginally up from 2019 ($26.5bn) and 2018 ($28.9bn).

Yet over the same period, as this share price chart makes clear, Vodafone’s share price has roughly halved meaning…well, who knows?

I understand that at a particular point in time, market valuations can be off kilter (witness Morrisons purchase this weekend at a price approximately 60% higher than in June) but over time, and certainly over four years, they tend to reflect the true picture.

So does this mean that Vodafone’s brand value and market value are completely out of sync? Or that investors are brand-illiterate and can’t recognise a strong brand when it stares them in the face? Or that they simply do not know how to value a brand?

Anyway, I asked Kantar if it could explain it to me, and this is what it said.

“Our valuations process comprises Financial Value combined with Brand Contribution (the survey-based brand equity component basically).One, for FV we use Enterprise value as one of the key components, which has been moving positively for Vodafone recently. Two, the brand’s brand equity has [also] been moving positively recently, which will also positively impact overall Brand Value.”

So there you have it. However, if you were a Vodafone shareholder I’m not sure you would find this much comfort.