Why ad block users are not all ‘militant ad haters’

The Media Leader Interview

The future of advertising is allowing the user to choose their own adventure, argues Marty Krátký-Katz, whose company is trying to help publishers claw back money lost to ad-blocking.

More than 820 million devices globally were using an ad blocker as of last December.

For Marty Krátký-Katz, CEO and founder of Blockthrough, a Toronto-based company that seeks to help publishers recoup ad revenue otherwise lost to ad block users by offering them an opt-in, “acceptable” ads experience, the issue is one of nuance and compromise.

“Being an ad block user myself, I don’t hate all ads, I just don’t like the annoying ones,” he said.

‘Every interruption has a cost’

Speaking over Zoom to The Media Leader, Krátký-Katz described how he, and many other digital users, feel about their online experience.

“As a user, I want to get to the information that I want to access as quickly and as interruption free as possible. And it’s the interruptions that really drive me nuts. So whether it’s a pop-up to subscribe and pay for access to content—that’s annoying—if it’s a pop-up that that says please turn off your ad blocker—that’s annoying.

“I want to be able to get to your news website, Mr. or Mrs. Publisher, with as few clicks as possible and as few interruptions as possible. And y’know, every interruption has a cost in terms of [audience] drop off, in terms of bounce rate.”

He cited internal survey data that showed that between 70%-80% of online users are willing to tolerate ads, but would prefer a “lighter ad experience” rather than, for instance, “get[ting] punched in the face with a pop up that says ‘Please disable your ad blocker'”.

Gravitating toward the most annoying experience

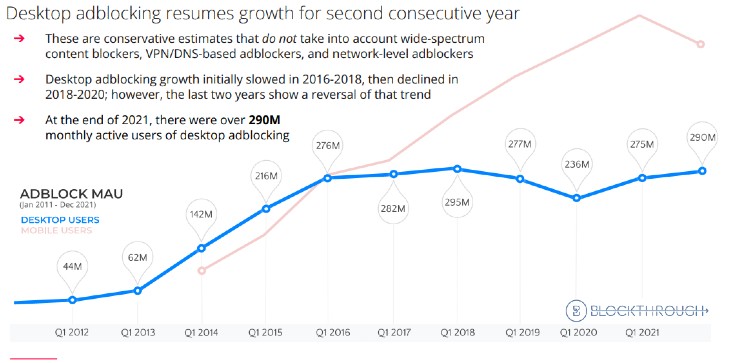

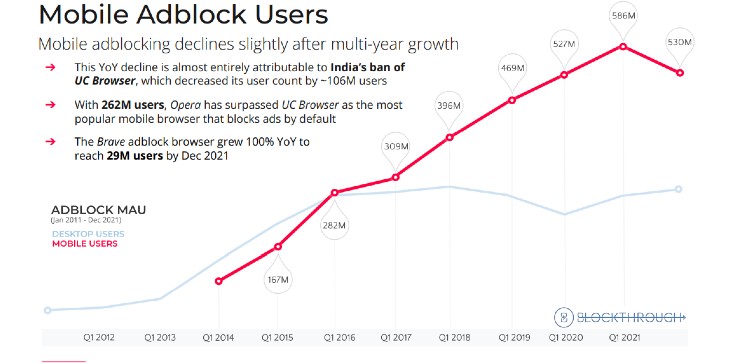

When Blockthrough launched in 2015, ad block use was on the rise. And, though it plateaued and eventually declined from 2016-2020, active monthly ad block users increased again in 2021 to surpass 290 million on desktop alone. An additional 530 million global users had installed ad block on mobile by the end of 2021.

“As long as there are no guardrails for the advertising ecosystem as to not allowing ad experiences to become overly obtrusive and annoying, then advertisers and publishers will naturally gravitate towards the most annoying experience because it’s what’s going to make them the most money in the short term, even though in the long term it might lead users to go and install software to nuke those things altogether,” reflected Krátký-Katz.

With so many users around the globe installing ad blockers, it’s only natural that publishers have sought to recoup some revenue through companies like Blockthrough, which programmatically filters back in ads that meet third-party standards created by the Acceptable Ads Committee, an independent non-profit that seeks to create and update industry standards “for respectfully monetizing ad block users.”

Krátký-Katz (pictured, below) is himself a board member of the Committee, and served as its president from 2018 until this July.

Blockthrough partners with ad block software companies to give users the option to opt-in to ads deemed acceptable by the Acceptable Ads Committee. Though Blockthrough doesn’t have deals with all ad blockers, including the popular uBlock Origin (its developer is, according to Krátký-Katz, a “militant ad hater” who has never agreed to any scheme that would allow users to see ads of any kind), it covers enough ground to have an impact on publishers’ bottom lines.

Krátký-Katz claims that in the past 12 months, the company has recovered more than $60m in publisher revenue, and that they are fast approaching $100m recovered for a publisher’s lifetime.

The success didn’t happen overnight; when Blockthrough was launched in its current state, “we had something like 29 days of cash left in the bank,” said Krátký-Katz. “So this was like the Hail Mary pass that if it didn’t work, we were screwed.”

The company was boosted by the Covid pandemic, as more publishers boarded their technology when adspend “fell off a cliff”, and they haven’t turned it off now that adspend is better.

‘Allowing the user to choose their own adventure’

About half of all display ads on the internet do not meet the creative requirements necessary to be considered compliant with the Acceptable Ads Committee. The number rises when other categories of online ads are considered.

“It’s basically a lot. A lot of the ads that we serve on the web are annoying to a lot of users,” reflected Krátký-Katz, though he recognized that “not every user has the same tolerance threshold for annoyance, either” and that advertisers and publishers need to meet individuals where they are.

“I think the notion of: we’ve built everything to be one-size-fits-all in terms of ad experience, that’s not a good way of building a sustainable advertising ecosystem,” said Krátký-Katz, adding that publishers’ and advertisers’ incentives to make as much money and receive as much engagement as possible conflicts with users’ desire for clean and quick access to information online.

“The reality is that engagement and annoyance are two sides of the same coin,” he appended.

Krátký-Katz advocates for better dialogue between consumers, who are represented by ad block companies they use to halt ads, and advertisers and publishers.

“The future of advertising is allowing the user to choose their own adventure and be monetized in a way that they are comfortable with, while also maximizing revenue for the publisher.”

‘A lot of education to be done’

Part of the challenge, however, is simply educating consumers in the first place about options for receiving acceptable ads.

While there are, as Krátký-Katz described, “militant ad block users” out there, they make up a strong minority (estimated 10%-20%) of ad block users. The rest are open to supporting publishers through ads so long as they don’t substantially harm the user experience, but they may not know to opt-in to an Acceptable Ads experience.

“I think there’s a lot of education to be done around acceptable ads [on the consumer side],” reflected Krátký-Katz.

In the meantime, publishers may continue to take note that compromises exist between themselves and their consumers.