Mental health crisis ‘worse than we thought’

The mental health crisis, spurred on by the pandemic, and now affected by a poor macroeconomic environment and other global issues like climate change and war in Europe, is worse than previously known.

Prior studies from the UK suggested that one in six workers suffer from an issue with their mental health in a given week, and one in four in a given year.

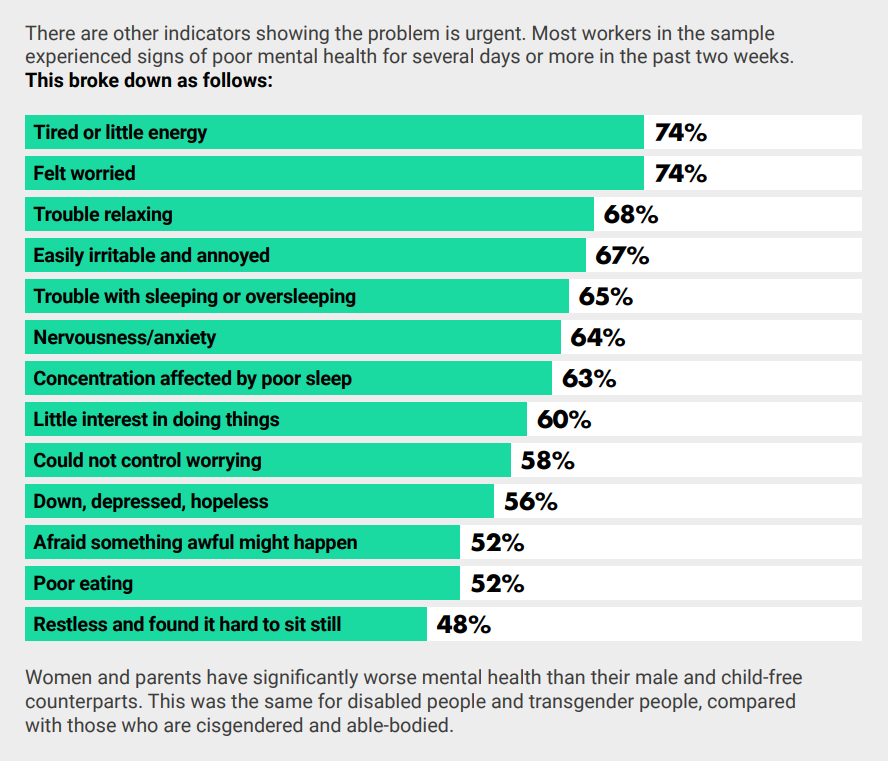

But according to the latest study conducted by culture change business Utopia and market research company Opinium, three in four employees are struggling with their mental health at work, with two in three saying that their employers are not doing enough to support them.

The study, which was released to mark World Mental Health Day, notes that four in five say their mental health has declined due to external events in the last two years.

The results are broadly in line with research from the Office of National Statistics, which found rates of depression in Britain doubled from one in 10 in March 2020 to one in five by last November.

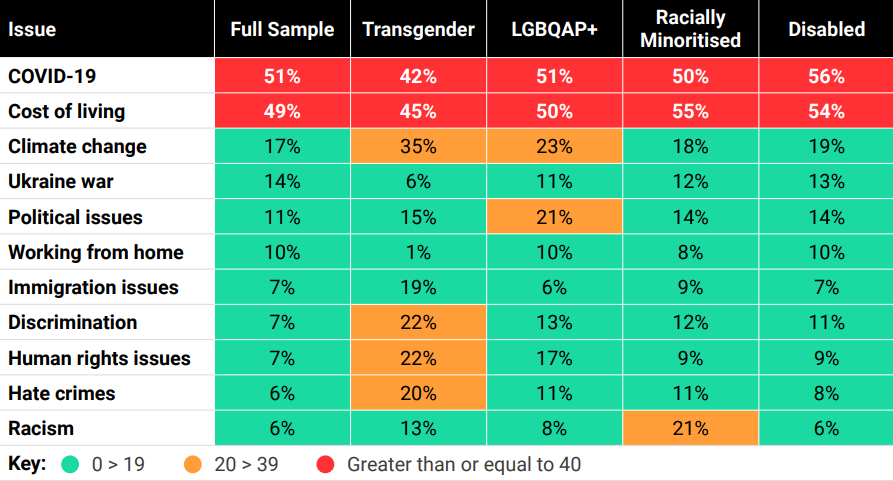

It also reports that disabled, racially minoritized, and LGBTQI+ individuals, as well as women and parents, have significantly worse mental health than their peers outside these groups. Furthermore, racially minoritized and transgender workers are most likely to say that workplace mental health initiatives would improve their mental health.

‘Blurring of boundaries’

The issue is particularly salient in the media and entertainment industries, which have seen a significant uptick in mental health concerns since the start of the pandemic.

In the past year, NABS, the UK advertising and media industry’s wellbeing charity, has received a 128% increase in calls relating to mental health.

“That’s a clear call that people in our industry are in need of help,” says NABS’ director of wellbeing services and culture change Lorraine Jennings-Creed.

“Adlanders have been going through so much, from the long-term effects of the pandemic to challenges experienced by those from minoritized groups.”

Jennings-Creed notes that hybrid working in particular has been an adjustment for businesses and their employees, which has added to anxieties for some, while alleviating pressure for others.

The blurring of boundaries between work and home have led many to feel the need to be “always on”, which can lead to burnout and impact retention rates, says Jennings-Creed.

Mental health concerns, namely burnout, have been speculated to correlate with levels of staff attrition “never seen before” in the media industry.

In an attempt to ameliorate the issue, some media companies have taken steps to more directly support their employees’ mental health. Examples include offering meditation and mindfulness sessions, educational lessons and resources for those who may be struggling, and ensuring that mental health first aiders are trained and available for anyone who may be struggling in the office.

For some, the additional support has been helpful. Louise Watson, practice director at Propeller Group and parenting lead at the Women in Programmatic Network, told The Media Leader that, after becoming a new mother at the onset of the pandemic, the transition to working from home after her maternity leave was highly challenging, leading to feelings of anxiety and doubt.

She credits the leadership team at Propeller for giving her the encouragement and space she needed to balance her duties of taking care of her child while also balancing her responsibilities at work.

“A year on, and flexible working has allowed me to prioritise my mental health,” says Watson. “The constant ‘mum guilt’ is lessened by the fact that I can still be there for my son for most dinners and bedtimes, whilst still giving the job that I love 100%.

“Being vulnerable and talking to the team about what is going on is not something that comes naturally, but it has become vital and is allowing me to juggle more effectively and more importantly not to feel guilty about having a life outside work.”

Others, however, find there is still a stigma in discussing their mental health issues with their employer and asking for support.

Almost half (43%) of survey respondents said they were not comfortable with talking to their line manager about mental health, and over half (51%) who take time off for their mental or emotional health do not tell their employer the reason for their absence—a significant difference from, say, needing to take time off because of a physical injury or illness, like Covid-19.

Certain demographics—namely minoritized individuals (-29%), working class individuals (-28%), and women (-24%)—were even less likely to feel comfortable speaking to their boss about mental health.

‘It is considered really normal to have breakdowns’

The lack of support is especially felt in the US, where norms around parental leave, vacation and sick days, and wellbeing are in general not as prioritized.

One entertainment industry professional, speaking to The Media Leader on the condition of anonymity, said that even when working for “the best possible employer, production assistants aren’t treated like people.”

They described a complete lack of autonomy over when and if it is possible to take vacations, time off for weddings and religious holidays, or even a simple 30-minute lunch break, leading to a high degree of anxiety, burn out, and isolation from friend and familial support systems.

“You have to forego any form of personal life or burn yourself out for a shot at a better job for very little pay,” they added.

While working from home has caused a blurring between work and non-work hours across much of the white collar economy, the issue has been particularly exacerbated in industries such as TV production, where executives are used to seeing work done on tight deadlines with little consideration for work-life balance.

“[W]ork hours didn’t exist […] I’m out on Saturday for brunch? Doesn’t matter, [my boss] needed the same email I’d sent the day before re-sent because they can’t find it. 11:00pm? Email time.”

The source added that it is “considered really normal to have breakdowns and cry at work at the lower levels [of staff],” due in part to lack of sleep, anxiety about the precariousness of job positions, low pay, and a lack of employee benefits.

Addressing core issues and causes

Utopia’s report recommends that businesses should not aim to “help people survive toxic cultures”, but rather institute systemic changes which require real investment.

While many of the solutions taken by companies—such as hour-long mindfulness sessions—can provide temporary improvements to mental health, Utopia suggests they are ineffective at tending to issues in the long term if employees return to a place where they may feel excluded, overwhelmed, and unsupported.

As such, the culture change business recommends a five step process for organizations to go about improving their workplace culture.

1. Conduct a business health check, with third-party support if needed.

2. Assemble a change-making team who have influence and interest.

3. Set goals and build a strategy with proactive and reactive elements.

4. Define limits and put protective measures in place by consulting specialist support where needed.

5. Look for easy wins while attempting to address the big picture.

Utopia and Opinium’s findings come from a quantitative and qualitative assessment of over 3,000 office-based, retail, and supply-chain workers across the UK.