Can the media really cover hate speech without amplifying it?

Opinion

Sunlight may be the best disinfectant in theory, but in practice it doesn’t quite work.

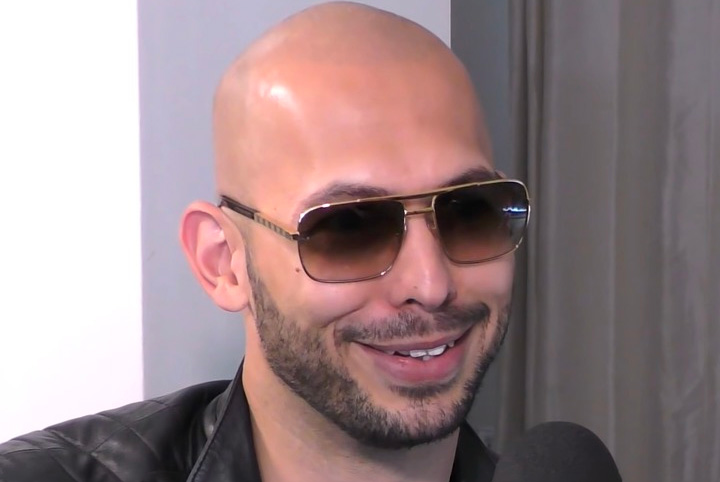

Last month, social media influencer Andrew Tate was banned from platforms such as TikTok, Instagram and Youtube after the depth of his misogyny came to light in the news.

Clearly it took too long for these platforms to spring into action — it took six years from his initial catapult into fame on Big Brother UK to getting shut down on platforms. Meanwhile, women are swiftly banned for sharing pictures of their own nipples.

But the fact that he’s received so much airtime in the media is something worth talking about. Most particularly, because it might have had the opposite effect than originally intended.

Born in Chicago but raised in the UK, the former professional kickboxer has never been shy about his hateful and sexist views on women. Currently under investigation for human trafficking in Romania (where he moved because laws against rape are more lenient), his videos, which perpetuate hate speech against women and other marginalised communities, have been steadily growing a following over the last few years without much consequence.

It’s only as several of his videos have gone viral — most of them touting extreme views about the place women have in society — that the social media powers-that-be have finally done something about it.

Losing the war on hate

Of course, the media played a large part in this. According to a Google search at the time of publishing, there are roughly 600,000 news stories about this distinctly average man — a mixture of simple reporting and op-eds calling for consequences against him.

It would follow then, that we, the media, should pat ourselves on the back. We did what was needed and, thanks to us, he no longer has a platform to share his harmful beliefs, right?

After all, it was Proust, wasn’t it, who said that to strip someone of their powers, you had to cut off their resources (or was that a line from Mean Girls? I forget. Women, hey. Useless, aren’t we?!)

But there’s something about the whole scenario that just doesn’t feel… right. I can’t shake the feeling that we, the general public and the media, haven’t actually won this war.

At last count, just before he was shut down. His Instagram account had 4.6 million followers, whilst on YouTube, he had an audience of 740,000 — both numbers that actually grew during the time Tate spent as a trending story. Thanks to this, I can’t help wondering if, by highlighting him in the press, he was able to gain more visibility.

This brings me back to one of the media’s ongoing and increasingly pressing problems: is it actually possible to cover hate speech in the news without amplifying it?

Media is being gamed

Most studies on ethics within journalism will agree that covering hateful, harmful or bigoted views without giving the perpetuator more power is a difficult line to toe. A lot of hate groups use the media as a tool to gain a bigger following, knowing that the more controversial and polarising the views they express, the sharper the outrage and the more extensive the coverage is likely to be.

And, whilst the idea that “sunlight is the best disinfectant” might have once been a generally sound one, it’s harder to hold onto now that social media is such an easily accessible tool — not just for the leaders of hate groups, but for their followers, as well.

What’s happened with Tate is a perfect example of this. Whilst he may no longer be able to share his views on social media, it hasn’t stopped others from doing so. At the time of writing, his hashtag on TikTok (a platform he never acutally had an account on) has had 15.8 billion views — up from 14.3 billion at the end of August, as ‘fans’ of his views (mostly vulnerable and disaffected young men) continue to spread them.

He may be banned on social media but his message certainly is not.

What makes this worse is the power that social media algorithms add to the mix. After researching Tate for merely a few minutes, my social media feeds — particularly TikTok — are now filled with similar videos on violent misogyny, since the algorithm now believes that’s what I want to see. Whilst I am not at risk of becoming susceptible to these views, many others are.

Sunlight may be the best disinfectant in theory, but in practice it doesn’t quite work.

The media might be able to prevent hateful speech from infiltrating the mainstream by bringing it to light, but that’s about where our powers stop. Because disease loves dark corners and by pushing it out there in the hope that it will be forgotten, we’re allowing it to breed and manifest at peace from prying eyes.

Bianca Barratt is a freelance journalist and editor and writes features across business, lifestyle and culture. A former lifestyle writer and shopping editor for the London Evening Standard, she is now a senior contributor to Forbes Women and has written for titles including The Sunday Times, Independent, Cosmopolitan, BBC Good Food and Refinery29. She writes for The Media Leader each month.

Bianca Barratt is a freelance journalist and editor and writes features across business, lifestyle and culture. A former lifestyle writer and shopping editor for the London Evening Standard, she is now a senior contributor to Forbes Women and has written for titles including The Sunday Times, Independent, Cosmopolitan, BBC Good Food and Refinery29. She writes for The Media Leader each month.