Cardiff University has settled the BBC bias argument once and for all

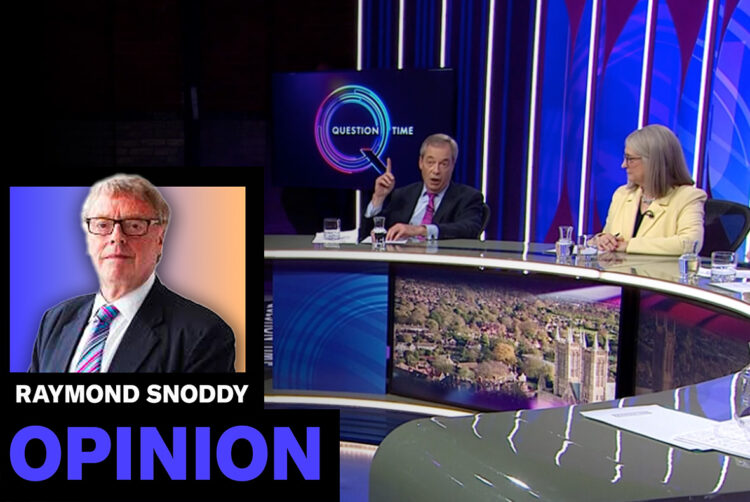

Opinion

BBC bias has always been a matter of opinion. What was needed was independent research and now we have some from Cardiff University. Its findings do have a clear outcome, but perhaps not in the way expected.

There is a suspicion, voiced frequently online, that the BBC’s Question Time is biased. Usually, the allegation is that it gives undue emphasis to right-wing points of view — although some have managed to detect a leftist conspiracy.

There have been complaints about the composition of the audience, which of course can influence which members of the public get to ask the panelists questions and the applause received by speakers.

The greatest controversy has involved the large number of times that Reform party leader Nigel Farage has appeared: 38 times — the vast majority before he was an MP in Westminster.

Then there are the frequent appearances from people attached to the “think tanks” of Tufton Street, usually tiny organisations with obscure finances and objectives.

What is the truth of the matter? Is Question Time an example of unacceptable BBC bias?

Until now, it has been really only a matter of opinion. What was needed was independent research and now we have some, from Cardiff University’s School of Journalism, Media and Culture, that could settle this particular debate.

What about Lucas?

An analysis of all editions of the programme from September 2014 until July 2023 — 352 episodes, with 1,734 non-politician guest slots filled by 661 people — does indeed produce a clear outcome, but perhaps not in the way expected.

The programme has roughly been given a clean bill of health on the selection of politicians used, with Labour and Conservatives well-represented across the nine series.

Among the smaller parties, the Scottish National Party was well in evidence. Although the Green Party did consistently appear each season, there was a decline from a peak of five appearances in 2015/16 to just one in 2021/22, despite its vote share growing to 2.7% in 2019.

Surprisingly, appearances by Farage-led parties — Ukip, the Brexit Party and Reform — also declined from a peak of 16 appearances in 2015/16 to just one in each of the last three years of the sample.

Equally surprising during the period of the research is that the former leader of the Greens, Caroline Lucas, appeared more often than Farage — something that would not be the common perception.

It would be surprising if both the Greens and Reform have not increased their visibility in the past 18 months, making a clear case for the research to continue.

Heat over light

The outstanding feature of the research, and one that could point to a potential breach of broadcasting impartiality rules, is the preponderance of right-wing commentators being used.

Those who appear most frequently tend to come from the political right and are typically opinion columnists who write for papers such as the Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph or appear on right-leaning broadcasters such as GB News and TalkTV.

The top five most frequently used panelists have all written for the right-of-centre Spectator and there is no comparable influence from left-wing publications. The most frequently used writers from the left were Novara Media’s Ash Sarkar and former Guardian columnist Giles Fraser.

The fact that the most regular panelists on Question Time are Isabel Oakeshott and Julia Hartley-Brewer, Cardiff rightly argues, “raises questions about how producers choose guests”.

At the very least, the overuse of those who write for right-wing outlets “suggest an emphasis on heat over light”.

Provocation over impartiality

Of course, under the present system of media ownership in the UK, it might simply be that more panelists considered suitable happen to be employed by right-wing media.

And not all of such people are totally incapable of independent thought and comment. The former editor of The Spectator, Fraser Nelson, springs to mind.

Matt Walsh, head of the School of Journalism, Media and Culture, notes that research on broadcasting impartiality has tended to focus on news programmes rather than political debate programmes.

“The commitment to due impartiality can indeed mean that impartiality occurs over time — but the evidence does not demonstrate Question Time is achieving this,” he says.

Instead, it suggests that the BBC may be sacrificing its reputation for impartiality “to create provocative programmes”, Walsh adds.

If the producers of Question Time and other related political chat shows want to avoid the attention of Ofcom, they should read the Cardiff research and have a care about what they are doing in the future.

For a start, they should not have on their programmes inhabitants of Tufton Street unless their paymasters are publicly known.

The forces against the media make 2025 a year to stand up and be counted

From news to non-news

The Question Time work is a telling example of the importance of independent, careful media research looking, over time, at the way daily-deadline journalists simply cannot do.

And once you start looking for research, there is a lot of it around.

Another respectable researcher is Enders Analysis, which this week produced a report on the importance of YouTube to the news business.

The research shows that YouTube is the UK’s fifth-most-used venue for finding news, although there is an unsurprising demographic element, with 16-24s ranking YouTube second as a means of finding news, while the over-55s overwhelmingly prefer BBC One.

There is what amounts to a bit of a catch in the emphasis British publishers and broadcasters give to YouTube.

For a start, according to Enders, YouTube algorithms tend to funnel users from news towards non-news content within a few videos — something that absolutely does not happen in reverse.

And, yes, you guessed it: YouTube is better for exposure and consumption than it is for actually generating revenue.

But at least there is no evidence of widespread brand-safety concerns impacting advertising on news videos.

Hitting a wall

Another piece of perhaps more obscure research — but important to those in the publishing industry who need to know such things — came this week from the media and communication department at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Neil Thurman, a British professor there, together with a team of researchers, tried to find the best strategy to maximise the sale of newspaper paywall subscriptions.

To summarise a long and detailed piece of work: you must not give too much information away as a teaser or that will be enough to satisfy the hoped-for subscriber without the need to press the “subscribe” button. Small gifts don’t have much impact either.

The thing that works best is a discount. Who would have thought it? But it’s always nice to have rigorous research to prove what you thought the best strategy might be.

Raymond Snoddy is a media consultant, national newspaper columnist and former presenter of NewsWatch on BBC News. He writes for The Media Leader on Wednesdays — bookmark his column here.

Raymond Snoddy is a media consultant, national newspaper columnist and former presenter of NewsWatch on BBC News. He writes for The Media Leader on Wednesdays — bookmark his column here.