Fixing the Internet: a practical guide for advertisers

Media Leaders

In the second part of Nick Manning’s thoughts on fixing the digital advertising landscape, he provides six recommendations for advertisers.

In last week’s column I described the advertising market as “dysfunctional” and set out the reasons why.

For anyone who still needs persuasion, this video goes further, deeper and better. Richard Kaplan of Arete Research is the ‘go-to’ guy on this subject and one of the truly independent voices. It’s time well-spent.

In a nutshell, the market has become extraordinarily unbalanced with the biggest winners on the supply-side of the equation and advertisers (the only true demand-side players) losing out, and much great and effective advertising has been lost along the way.

Paid-for advertising is not the only way to attract attention, but it is booming right now; while it is good to see television doing so well, we shouldn’t allow short-term trends to distract from the underlying challenges we face.

The successful symbiotic relationship between advertisers and their commercial partners has been fractured by the Klondike in the digital market, where vast profits are being made at the advertisers’ expense.

While systemic industry change and much-needed regulation are a distant prospect, individual advertisers can, and should, aim to address this imbalance for themselves. By happy chance, the solutions can be clustered under the letter ‘T’.

Firstly, this is not about ‘digital’ or ‘traditional’ media, but about good and less good places to advertise, so all of these recommendations apply to all media.

However, the majority of the issues arise in the quagmire of digital.

First up is truth and trust. The internet has become the home of disinformation, enabling virtually unfettered access for anyone with an opinion to ‘publish’ their views and the more outrageous they are, the more traffic they generate to turn into ad revenue.

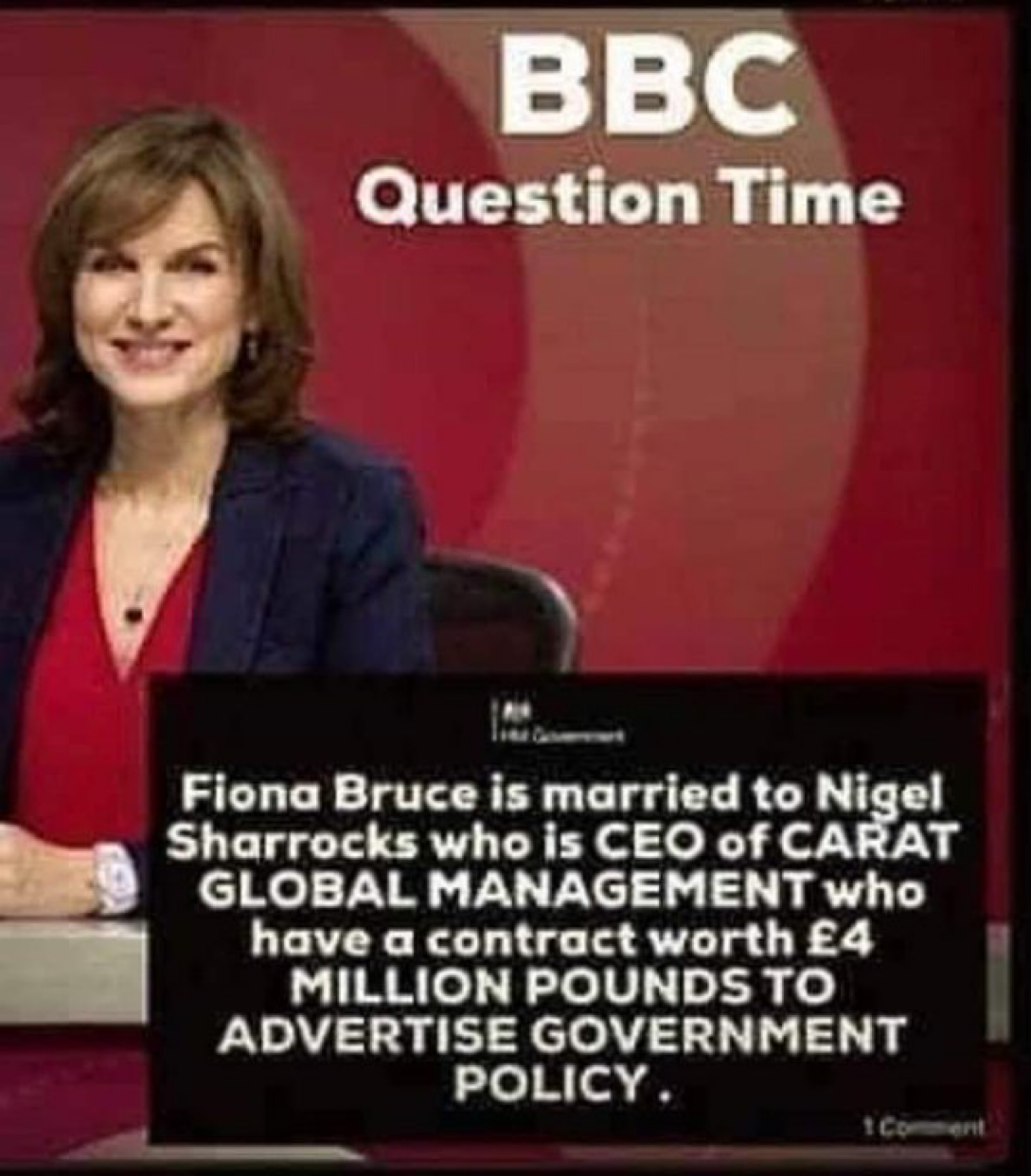

An example close to home. Social media postings show that some viewers of BBC’s Question Time find it biased towards the Conservative government and have worked out why. Apparently, it is because Fiona Bruce is married to Nigel Sharrocks, who is supposedly CEO of Carat, which has a £4m contract with the Government for ‘PR’.

So Fiona, it is claimed, is simply parroting the party line to further her husband’s interests.

However, most of you will know that Nigel left Carat over 10 years ago, four years before Carat even won the Government contract, which they then lost in 2018.

You will also know that HMG’s media-buying contract has nothing to do with ‘PR’ and is a neutrally-run enterprise.

But that’s not the point. The sad truth is, that even if any of this were not laughably irrelevant, the likelihood of Fiona Bruce running Question Time on the basis of personal interests are nil. The ‘story’ is ridiculous in every respect, but it’s a tiny example of the ludicrous extent that social media has poisoned public opinion and arguably even infected mainstream media as they derive so much of their content from that source.

People no longer trust what they see or hear, even on Ofcom-balanced channels such as BBC One, and this endemic scepticism has contaminated advertising. Research shows that public trust in advertising has declined in recent years.

So what can advertisers actually do about this?

You’re known by the company you keep

In the same way that truth should be a cornerstone of an advertiser’s messaging, brands should advertise in environments where the truth is valued

This means actively choosing high quality environments where content creation and curation are based on objectivity and balance. This obviously applies especially to current affairs but the quest for high-quality of surroundings should apply to all media and genres.

People judge you by the company you keep.

Yes, this may mean using fewer channels and reducing investment in those which rely on user-generated content, but this would be a long overdue correction. Advertisers spend weeks honing their creative materials, so it seems only logical to spend the extra time making sure it appears in an equally considered location, not just sprayed out by programmatic machinery.

Does public trust automatically follow? No guarantees but the alternative is to carry on as before and not even try.

The result is better advertising in a healthier environment, those media owners who value and invest in high-quality content get the money and the public has a better advertising experience. And advertisers no longer fund toxicity.

Let’s talk about transparency. It’s a shame that this word has become so strongly associated with the financial relationship between advertisers and their media agencies. This rather underplays the end-to-end need for transparency over which media agencies have less control.

In its fullest sense, transparency encompasses the ability of advertisers to track and measure the full extent of where their data and money flows.

Given the numerous links in today’s digital ‘daisy chain’, advertisers need to understand where their money is spent and what they got for it, right down to the nuts and bolts of viewability and ad fraud in the online display market.

It’s very hard to achieve this right now and vested interests in the supply-chain actively prevent it. The Walled Gardens have grown enormously despite their refusal to provide the kind of data advertisers need.

Get serious about demanding transparency

Advertisers should task their commercial partners throughout the supply-chain with the provision of full visibility and only work with those partners who actively provide it.

This often means going off the beaten track and working with lesser-known players, but the rewards are there with the right set-up and willing partners.

The ISBA Media Services Framework is a good starting-point and the addition of a detailed scope-of-work and service level agreement that priorities transparency of planning and delivery is an additional necessity.

Taking these steps should eliminate residual trust issues between clients and agencies, lead to impartial media planning and optimise spend, thus saving money.

Let’s talk about technology, tracking and testing. Possibly one of the least helpful contributions to modern-day advertising was the Lumascape. It led people to think that adtech was an impossible maze to get through and that all of the various links in the adtech chain were necessary. It was designed by an investment bank for its own purposes, and has no doubt been wildly successful for them.

The reality is that the technology that advertisers need is not very complicated as long as the people guiding advertisers through it are doing so in the client’s best interests by simplifying and clarifying the process while looking for effective solutions and efficiencies.

Media agencies set up ‘trade desks’ in the earlier years of online display and these acted as a highly profitable obstacle between advertisers and the new supply-chains that deliberately obfuscated what was going on. Some progress has been made but not enough.

While matters have improved through advertisers insisting on more transparency, the complicated web of contractual relationships in the middle of the Open Web display market continue to be a source of both financial loss (see ISBA/PwC 2020) and the inability to track and monitor advertising results.

Part of the imbalance in the market is the 50% erosion of money in the supply-chain between advertiser and publisher and the almost complete absence of visibility over the arbitrage on media costs that enables the big adtech players to make incredible profits over and above their take-rate.

The actual loss to advertisers including arbitrage is probably a lot more than 50% even before the deleterious effects of poor viewability, ad fraud and other exposure issues.

Much of what is being bought in the Open Web is quite literally worthless but low cost currently trumps effectiveness. We are still using metrics such as the MRC definition of viewability (50% of the ads for 1 second etc) that favour the publishers, not the advertisers.

We still don’t have industry-level consensus on what constitutes a ‘quality CPM’.

We have an industry that needs to produce more impressions than there is demand for, often to fulfil revenue targets for adtech businesses who want to float or have. So impression flow is the only thing that matters, and never mind the source or quality.

The adtech players get paid whatever the quality of the impressions they process and the harsh reality is that it is not in the interests of publishers, adtech companies or media agencies to know what the truth is about invalid traffic.

Only work with partners that provably add value

Advertisers should task their commercial partners with reduction in the supply-chain to only those elements that add value, and know what value they add.

They should set ad exposure metrics that represent true viewability for their creative assets and be prepared to reduce volumes while accepting a true price for high quality exposure.

While visibility of the supply-chain will remain elusive until advertisers get better information and the right to audit, they can and should ask their media agencies to set up the best and most transparent sources of relevant inventory supply and tools to measure ad quality.

Yes, this means no longer deferring to the default options of Google, The Trade Desk and Double Verify/IAS and instead selecting partners and vendors who don’t just press buttons for a living. It means only paying for verified impressions that hit the right thresholds of veracity and viewability.

There are other vendors in the ‘content verification’ market who are more brand-side focussed and not beholden to big publisher contracts that set a low bar for viewability and fraud.

Advertisers should take control of their tech stack, demand transparency of data, money and ad quality and interrogate their supply-chain until it confesses.

With regard to the Walled Gardens, and given their walled-ness, it is imperative to measure, test and optimise on a continual basis and only rely on the advertiser’s own evaluation of effectiveness, especially given the erratic and risky nature of user-generated content and its effect on attention.

The benefits are multiple, including better optimisation towards effectiveness, less wastage, more money going to the right publishers and better measurement. Why would anybody not do this other than the vested interests of the supply-chain?

Let’s talk about testing. Most advertisers will by now have a decent testing programme in situ if they are using multiple channels, pieces of copy and have good measurement techniques for their business objectives. It goes without saying that this becomes even more important when using Dynamic Creative Optimisation.

However, the question arises as to who conducts the testing and how the results are used in optimisation.

Use measurement experts to navigate a quickly-changing world

Advertisers should employ in-house or independent experts who are able to evaluate the full range of content and channel combinations in order to provide a set of results that can be used across the client organisation.

This should include the contribution of other factors, including the influence of customer experience and other marketing disciplines that affect performance.

While marketing or media mix modelling can still play a macro role, especially if looking at the wider picture of product and price, for example, testing programmes should recognise the limitations of such techniques and include other statistical methods that are better at measuring digital channels.

The measurement world is constantly changing and advertisers should consult with outside parties continuously on new techniques, such as the measurement of attention. It goes without saying that they should participate actively in industry-wide initiatives such as Project Origin.

Next up, talent and training. All of this takes a high degree of expertise and skill and there is currently a dearth of people with the appropriate qualifications.

[advert position=”left”]

However, we are fortunate in the UK to have a disproportionate share of the most experienced people, and advertisers are able to offer more rounded career paths to people in the broader areas of marketing.

Some ‘digital natives’ are as yet unversed in the wider world of marketing and media and may receive better education in a client company.

While the in-house movement has lost some of its over-vaunted impetus, the one area where advertisers should invest in is in-house analytics, working with the agencies’ own people to find a common ground on performance.

Invest in effectiveness

Advertisers should invest in people who are able to improve marketing effectiveness in collaboration with their agencies, whereby the investment is self-funding.

Most clients don’t have the financial agility to recognise that optimisation can lead to substantial efficiencies, with the option of reinvesting the proceeds to fund other disciplines. It shouldn’t be hard to rectify this.

They should also employ T-shaped people who can specialise in their craft while working well within a broader team, especially when nurturing people for wider roles.

They should also be highly involved in the composition and cultivation of the agency team on their business, leading to better relationships and greater longevity.

Equally, advertisers should place a strong emphasis on employing agencies who subscribe to the approach outlined in this piece and who inculcate these practices in their people. The best client relationships arise from informed discussion between client folk who are suitably qualified and their agency counterparts.

And, finally, terms. Everything costs and the prescription set out in this column requires investment.

It is a sad reality that most advertisers underpay their media agencies for the total contribution they make. This is a problem largely of the agencies’ making, given that for many years they undercharged for some services when media buying margins, declared or not, were handsome.

They set an unrealistically low fee bar and are suffering the consequences now. They also set unrealistic fee expectations for independent agencies not playing the rebate game.

Advertisers have also been responsible for treating media as a commodity, and thinking that ‘media buying’ and low cost media were the core disciplines. This is still often the case and it is one of the reasons why low online pricing leads to the accumulation of worthless inventory.

However, today’s media agencies have to provide a highly sophisticated, data- and analytics-led service across multiple channels, with a high degree of experience and skill. We have great people in the industry but it’s a tough world where alternative employment, often better-paid, is available.

If agencies are to seek better solutions that rectify the current imbalance in the advertising market they have to spend more time looking at alternatives to the default, volume-led models. True value lies in the level of application that identifies better ways to improve results and avoid the pitfalls described earlier.

Reward agencies properly

Whatever the fee history within their organisation, advertisers should aim for savings from optimisation (not from agencies’ fees), and reward them for effectiveness and efficiency.

Higher fees can be self-funding if measured as part of the benefits of better performance. Greater financial agility is required to make this happen but, correctly measured, the results should speak for themselves.

Advertisers who pay disproportionately more will get greater attention from their agencies and will be allocated the right people for the job.

Okay, it’s hard to turn around a tanker; these six recommendations won’t fix everything but they are a good place to start.

However, it takes a strong programme and senior client personnel determined to improve. If these are absent, very little will happen.

To conclude the points covered in my two-part feature, we live in the converged age of Television, Tik Tok, Twitch, Twitter and other platforms that don’t begin with ‘T’ and life has changed irreversibly. Arguably the way that our industry works has failed to keep up thanks to legacy models and the imbalance of the market.

Industry-level change will happen thanks to the efforts of the advertiser trade associations, but it will take time. Regulation will take even longer, given the vested interests involved.

So advertisers who care will have to drive ahead with their own tangible transformation programme with the technical assistance from without.

The last two ‘T’ words are ‘time’ and ‘today’. We have lost too much of the former and can start to catch-up if we start with the latter. With suitable leadership 10 can be turned into 20 in 2022.

And if we can fix the Internet, we may even end up with a ‘Better-verse’ for when it becomes a reality for more advertisers.

Nick Manning is the co-founder of Manning Gottlieb OMD and was CSO at Ebiquity for over a decade. He now owns a mentoring business, Encyclomedia, offering strategic advice to companies in the media and advertising industry. He writes for Mediatel News each month.

Media Leaders: Mediatel News’ weekly bulletin with thought leadership and analysis by the industry’s best writers and analysts.

Sign up for free to ensure you stay up to date every Wednesday.