The ‘truthpaste’ is out of the tube: how advertisers should deal with the crisis of truth in media

Opinion

‘Truth decay’ is irreversible and we have to learn to deal with it. Advertisers, whose money funds the lion’s share of commercial media, can do a lot more.

Today’s exam question: what is the World Economic Forum (WEF)?

Is it a) a global pressure group combining government and private enterprise which comes together (usually in Davos) to think through the bigger challenges facing mankind?

Or b) a sinister global cabal dedicated to world domination and the suppression of the people of the world, led by billionaires such as Bill Gates and George Soros?

If you are an avid follower of social media, you may be inclined to think that b) is the ‘right’ answer.

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence for the conspiracy theorists on social media. The WEF narrative is nonsense, but what is different this time is that the conspiracy theories are starting to bleed into TV, the most persuasive medium of them all.

What’s more, the gap between TV and online distribution is increasingly porous. TV content is now made for online dissemination as a priority.

For example, on GB News the lugubrious Neil Oliver routinely delivers monologues that purport to describe how ‘they’ will take all of our possessions and turn us all into slaves of the New World Order, and close down our pubs and fish and chip shops (yes, really).

As a licensed broadcaster, GB News is supposed to provide a balanced view, but I suspect that they have not found time to find someone to defend the WEF, and no-one from the WEF is going to bother appearing on a channel that has zero credibility and roughly the same audience.

As Stephen Arnell speculated in his article, OFCOM seems to have decided that GB News does not matter enough to regulate. Perhaps it has decided to follow OFWAT and OFGEM in providing the light-touch regulation so beloved of our current government. What could possibly go wrong?

Meanwhile, TalkTV is part-radio station, part TV channel and part-online platform, a hybrid format that is virtually impossible to measure and regulate. They must hope that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Obviously none of this would be possible without social media. It was supposed to democratise comment and debate, but instead it has led to a creeping infantilisation of political discourse. Where nuance is required none exists as the algorithms suppress discussions that aren’t car crashes that spike traffic.

A crisis of quality

The conundrum is that the serious journalistic players who value proper impartial insights are beholden to the big digital platforms for their audience and revenue (reduced by the platforms’ share).

As the Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism has examined, many journalists believe they are in a no-win situation as they provide content for platforms that undermine them and reduce people’s trust in the news.

This subject was eloquently set out in the recent speech that Emily Maitlis gave to the Royal Television Society. The early headlines were all about the way that the BBC has kow-towed to the Government, but most of the speech analysed the way that politicians have routinely and deliberately twisted the truth to meet their agenda, leaving the media flat-footed in a one-sided competition where only one player tries to find the truth.

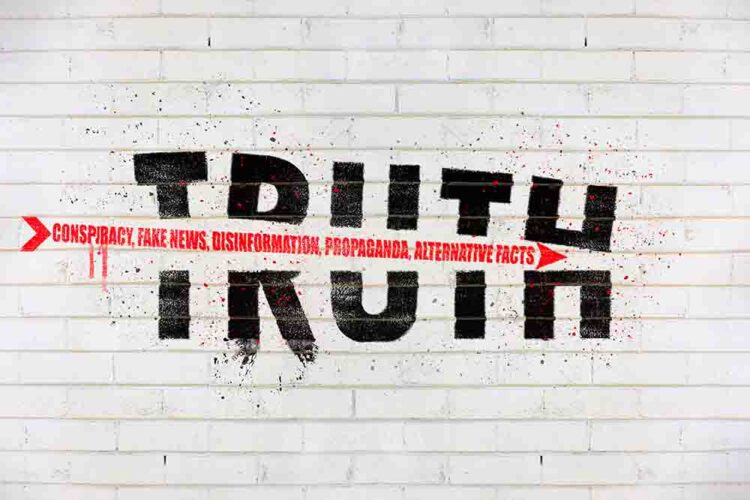

There is a crisis in the media world where high-quality analysis and impartial insight are on the run, and it is too late to turn back the clock. ‘Truth decay’ is irreversible and we have to learn to deal with it.

In this world, advertisers play a key role. Ad revenues sustain the internet-led media world but the algorithmic systems that underpin ad revenues favour sensational content over high quality reporting.

To counter this trend towards disinformation advertisers should take a stand and be more assertive about where they direct their investments in order to help maintain a healthy media eco-system.

This is now becoming a serious dilemma. In the past advertisers took the view that they should not take sides and if a medium delivers their audience, they should not take into account the editorial stance. The issue was framed in terms of ‘brand safety’, but now it is a far bigger ethical matter.

Time for adspend to align with brand values

Now advertisers should actively ‘defund’ (to use today’s clunky jargon) those media vehicles who seek to disseminate the kind of disinformation which erodes public trust in media.

They hold the most powerful cards in the pack, the ‘ad dollars’ that fund the internet-delivered media that are a key cause of the problem.

Clearly this speaks to purpose and values. Today’s companies not only pride themselves on their corporate reputation but they also have to fulfil their shareholders’ ESG-led needs.

But there is no point defining corporate values precisely and then spending ad money in ways that ignore them.

I’d like to think that any serious advertiser would understand why the rout of truth in media is so important and have a point-of-view on how they address it. However, there is often a gulf between the public statements they make and the practicalities of the market.

There have been a number of great initiatives to address this issue, such as The Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM) and The Conscious Advertising Network CAN), operating at an industry level. More recently, Brands4News has launched to rectify the problem of exclusion lists that aim to avoid ads appearing in the wrong environment (eg coverage of Ukraine) but which penalise legitimate news publishers by limiting their revenue.

NewsGuard provides an interesting scoring system that aims to evaluate publishers on a nine point set of criteria, with human monitoring that avoids the algorithm SNAFUs from systems that rely on Artificial Intelligence. Ebiquity has launched a service that helps advertisers fulfil their ESG needs, including the avoidance of media that spread disinformation.

These are all good initiatives, but individual advertisers should go one step further and direct their media investments away from the worst purveyors of disinformation, irrespective of their audience delivery.

The danger for advertisers is that they respond to the ‘sensationalisation’ of news media by attempting to take advantage of it, and automated media trading makes this happen.

We need the right tools and people

The answer lies in how advertisers set media strategy and planning, not in media trading. The latter should of course be a function of the former, but often is not in a world where agency volume deals trump plans.

At strategy stage, advertisers should charge their media agencies with the task of planning in a way that supports the right kind of media content by being far more selective on inclusion, not exclusion.

This should consider the best showcasing for the brand and the avoidance of the wrong kind of content, but it should actively avoid known purveyors of disinformation, even if such content leads to bigger audiences (‘car crash’ media).

Editorial content that is sensational also overwhelms advertising around it.

Media agencies should use like NewsGuard and Brands4News to guide their choices and curate media plans that meet the clients’ needs for ethical behaviour.

And they should ensure that the media agency uses buying techniques that deliver against this objective. This means far less ‘spray and pray’ and much narrower inclusion lists that can be bought via direct deals.

Media agencies should be required to report in detail on their success in achieving this, with exceptions highlighted. This includes the Walled Gardens, where the absence of data should be challenged.

This means (surprise, surprise) that clients must employ the right people and tools to ensure this happens. If they don’t, it simply won’t happen.

It is still the case that many advertisers do not control their adspend appropriately and do not know where their advertising is appearing. Online campaigns typically use many thousands of sites to supposedly build reach, exposing themselves to appearance on sites that contain deliberate misinformation and are riddled with fraud.

The online advertising eco-system is built on the volume of traffic and it is in the interests of the supply-side players (including the media agencies) to open the taps and let the impressions flow, with the associated risks to brands and the inevitable funding of nefarious content at the expense of the good guys.

Making marketers accountable

Media-buying practicalities are riding roughshod over attempts to plan more responsibly.

Some performance-based advertisers will continue to blast away and not care what damage they inflict, nor even if they fund fraudsters, if the conversion data (real or not) meets their needs. This makes it even more crucial that the big brands should spend in the best way to provide a healthy advertising environment for everyone.

Crucially, advertisers should seek media channels who value the truth and work hard to provide content that informs audiences appropriately in a messy, complex world. Logically, they should also actively aim to deprive the bad guys of revenue, as ‘Check My Ads’ advocate.

This all might seem naïve. Media agencies are under enough pressure already and planning and buying with such precision is a big ask. So advertisers need to invest in the right kind of services with the right monetary rewards if they are to fulfil their commitment to upholding ethical standards.

After all, a principle isn’t a principle until it costs you money. If I were running a corporation I would be charging my marketing teams with ensuring our advertising not only appears in the right places but actively ‘defunds’ the bad actors. And I would expect my marketing team to be accountable for this and able to quantify the effects.

There is nothing more important than the truth and we’re losing it. Once it’s gone the ‘truthpaste’ really is out of the tube.

Nick Manning is the co-founder of Manning Gottlieb OMD and was CSO at Ebiquity for over a decade. He now owns a mentoring business, Encyclomedia, offering strategic advice to companies in the media and advertising industry. He writes for The Media Leader each month.