Noam Bardin has a vision for supporting news publishing on social media

The Media Leader Interview

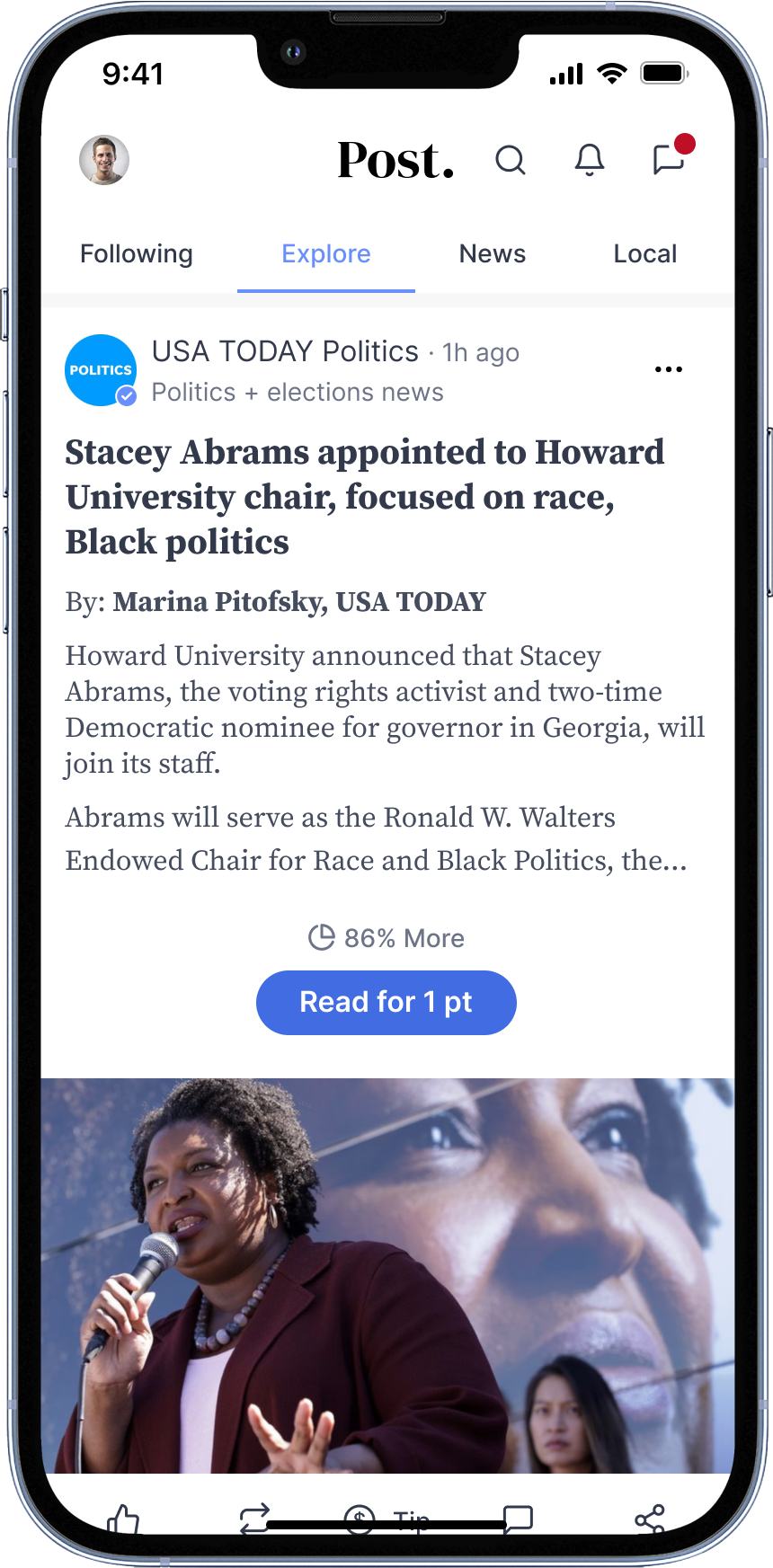

Post founder and former Waze CEO Noam Bardin discusses the transitioning state of social media, why publishers need to be considering micropayments, and how he felt compelled to create an alternative to the ‘tremendous damage’ done by the likes of Twitter and Facebook.

“We can’t just give the public squares to the fanatics and assume that everything will work its way out. It won’t.”

Noam Bardin founded Post, a social media platform “built for news,” last November. Just weeks earlier, Elon Musk had bought Twitter, and in the ensuing chaotic months, journalists, publishers, celebrities, and brands that once relied on the site are seeking greener pastures.

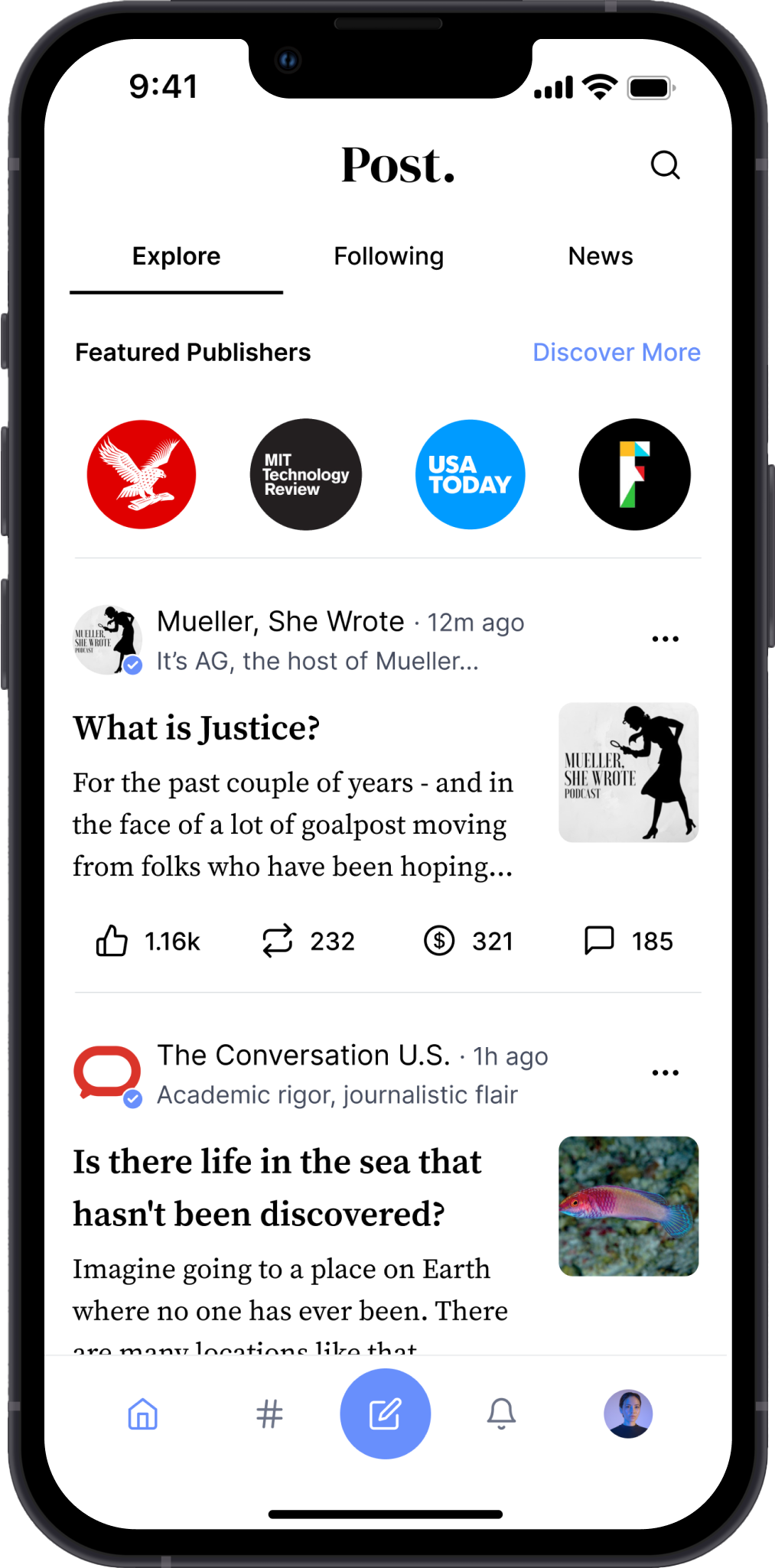

While Post has not yet reached a ‘critical mass’ of users, Bardin’s offering is attempting to bridge the gap left by Facebook and Twitter, which have deprecated news on their platforms, to allow for readers to access aggregated reporting, analysis, and opinion from sources they follow while also providing a much-needed new revenue stream for publishers.

In a wide-ranging conversation, Bardin spoke to The Media Leader about the state of transition social media finds itself within, and why local and ‘middle-tier’ publishers should be considering a micropayments revenue model in order to compete with increasingly ‘monopolistic’ big brand publishers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal.

Bardin also laid out Post’s own business model, revealed how the company is looking to add location features to allow local news outlets to better reach users, and explained why the increasingly toxic online environment drove him to create a place for ‘regular people’ to obtain aggregated news via a social platform that emphasizes trustworthy, reliable news.

The full conversation, edited for clarity, can be read below:

Jack Benjamin: It’s been nearly a year since you first launched Post on desktop. What have been the biggest challenges in trying to grow the company?

Noam Bardin: We’re in a transition phase in a few different things. One, I think we’re at the down arc of the original social media companies, and I personally think that’s a good thing. I think they’re responsible for a tremendous amount of damage and really are the source of a lot of evil.

But I think the more that social is not a product anymore; it’s a feature of many products. And what used to be a standalone product is not going to happen again. So I don’t think there will be another Twitter or another Facebook or another Instagram; there’ll be other companies, and if tech is really about bundling and unbundling, I think we’re in the unbundling phase, where companies are taking use cases from social and turning them into standalone products.

TikTok is the best example; TikTok is not YouTube, it’s something very different than YouTube. But it basically took a use case of YouTube, the short-form video format, and turned it into something completely different. It uses social, but differently. I think this is the change that we’re in.

Part of that change is in consumer behaviour when it comes to news. With Post, what we want to do is unbundle the news consumption on social. There wasn’t a platform for that, for people who want to consume their news on social—meaning, from lots of different types of sources, not just publishers, but newsletter writers and experts and creators. People, especially younger people, want to consume their news on social, but the current platforms were not built for news, and are actually anti-news in many different ways. And that’s really the fundamental change that we’re looking to build upon.

There are three that we see as the problems with the current platforms. The first is the user experience. When you’re on Twitter or Facebook and an article comes down your feed, it’s not really an article, it’s a link. You click on the article, you end up going to another website, getting bombarded with all these ads and email capture forms and all the fun user experience when you get there, just to hit a paywall at the end. That makes sense to me, because I’m 52 and I grew up with that expectation, and I subscribe to news sites.

JB: I do, too.

NB: Well, you’re very mature for your age. But my daughters are in college and they have no idea what I’m talking about. This concept that you’re paying someone to tell you what to read out of their universe of content is foreign. For them, it’s really about trusting someone that you’re following, and the fact they’ve shared an article with you is why you want to read it, not because the article was written by The New York Times. This is a fundamental change in how consumers associate with brands and I don’t think the media has caught on to it.

So, when we think about the user experience, we think that everything should be accessible within the feed. You should not be jumping around through different websites.

So, when we think about the user experience, we think that everything should be accessible within the feed. You should not be jumping around through different websites.

The second challenge is the business model. The current social media platforms were not built to compensate creators and publishers. They’ve also sucked most of the money out of the advertising space. But it’s even more extreme because it’s not in their interest for you to click on those [news] content units. That has led to all the different kinds of harm we’ve seen around news. It’s also created this false impression that a heavily researched opinion on TikTok is equivalent to a journalist at The New York Times. It’s not the same, but it looks the same on social.

That’s why we built a micropayment network into the product itself. The attempts at micropayments up to today have been standalone networks, and the problem with that is that it doesn’t solve the friction problem. The biggest problem when it comes to paying micropayments is friction. Sites that allow you to send money via Venmo to someone, for example; no one’s going to actually sign up and put their details in to send a small amount of money, but if it’s 25 cents with one click, well we’ve learned they will.

We borrowed our micropayment model from gaming networks like Twitch, trying to get simple, seamless, fun, tiny transactions.

The third challenge is toxicity. The current platforms make their money via toxicity; it’s a feature, not a bug. What their algorithms will always learn is that if you show people hateful content, they will stay longer on the platform. They’ll hate themselves, they’ll hate their neighbours, they’ll hate society, they’ll get a warped view of the world, that everyone’s terrible. But they’ll spend more time and watch more ads. And that’s the only thing that drives these platforms on any level. So that’s the third component that we’ve invested a lot in, is really fighting toxicity and being able to build a platform for what we call us ‘regular people.’ Not culture warriors who are going to spend five hours a day on social, but people that have jobs and families and other interests, but do want to consume their content from social, and enjoy what social has without making this a full time profession. That’s really our target audience.

JB: Who do you see as your primary competitors? Because a lot of the coverage that I’ve read about Post seems to be framing the platform as a Twitter competitor, but from my experience with the product, that seems to not really be giving it full credit. Because to me, it focuses on newsgathering to a degree higher than other social platforms and is also a product for publishers through offering a micropayment tool. Do you see yourself as more in the category with Twitter competitors like Threads, Mastodon, or Bluesky, or more like something akin to Artifact?

NB: We’re a bit closer to the category with Artifact.

We think about what news looks like in a social age. It really is a mindset of how you’re valuing the world. If you’re valuing the world through the mindset of Twitter alternatives and who’s going to build a new Twitter, we get lumped in with all of those clones. But I personally don’t believe that there is room for clone products. Twitter was Twitter because of the time it was created and the technologies and culture at that time.

That’s the biggest problem I have with the Mastodons and the Blueskys and the Threads of the world. There will never be another Twitter, there will be something else; same for Facebook and Instagram, et cetera. That’s really what a lot of these platforms are missing. There’s an inherent assumption with Mastodon and Bluesky that the problem with Twitter was it wasn’t federated. I don’t believe any consumer has ever come and said, Oh, I wish my product was federated, let alone if they even understand what ‘federated’ means. People want a product that works. They want a product that fills a need.

I think federation is very interesting, and we plan to support whatever protocol on it comes out, if it ever gets traction, but I don’t think that’s the problem. And it also has like this weird assumption that Twitter was a healthy place before Elon Musk came along. We all love to to blame Elon Musk, and I mean, I give him full credit for the blame he gets. But before he came, the company had a challenging business model. It was a source of toxicity and misinformation and disinformation and doxing and racism, et cetera. It’s gotten worse, but it’s not like it was great before. This is why you can’t like replicate the same things; you’ve got to build.

JB: Twitter’s business model was never really profitable. I’m curious how you view your own business model. Do you take a scrape of the micropayments that people might pay? How else do you earn your money and how do you see getting toward profitability for your own platform?

NB: First of all, we’re very early in terms of profitability, but we believe business models drive behaviour, and so you have to be very clear with your business models from the beginning; if you try to tack it on at the end, it creates a different type of incentive. For us, when you buy a bulk of points (the in-app currency by which users can spend to read non-free articles), we take a percent of the transaction. From that point on, it’s between you and the publisher or creator. The publisher sets the price, the publisher sets the model, you can decide to tip the publisher or purchase the article. We don’t want to get between the user and the publisher. We want to give them lots of tools.

In the future, we’d like to add algorithmic pricing so publishers can target users with the right price for them. We have a lot of different ideas of what we’d like to do. What has surprised us the most in our first 10 months is people’s willingness to pay and tip. When it comes to tipping, what we see is this whole economy where people enjoy tipping.

In the future, we’d like to add algorithmic pricing so publishers can target users with the right price for them. We have a lot of different ideas of what we’d like to do. What has surprised us the most in our first 10 months is people’s willingness to pay and tip. When it comes to tipping, what we see is this whole economy where people enjoy tipping.

We convert everything to CPMs, just to make it easy for publishers to compare. Publishers earn on average a $45 CPM, which very few publishers get in the real world. But even when they offer free content, publishers still earn a $2 CPM off of tips. Imagine tipping CNN, or tipping The New Yorker. Tipping an individual creator I always assumed would be part of it, but I’d never assumed they’d tip a brand. But they do.

We’re very early in figuring this stuff out, but from what we’ve seen so far, everything on the micropayment side has been surprisingly obvious to users. Before I started Post, I was going to build a micropayment network, like everyone else had done and failed. I spent a lot of time talking to publishers and the big question was whether people would be willing to pay anything. Would anyone be willing to do that? But consumers completely get it. With the paywall model, readers always say, I just want to read that one article, why can’t I just read that one article?

This goes into the basic problem with the current publishing space where every publisher assumes they’re going to be a destination site. You’re going go to me, I’m going to give you all your news, you’re going to subscribe to me, you’re going to open up my app or my website every day for your news, like you did a piece of paper. But that’s not how consumers want to consume today. They want multiple sources and different topics in their feed, personalised to them. And frankly, they don’t want to subscribe to 10 different sites.

We can’t continue to analyse the world from two business models — ads and subscription, that’s it. Every piece of content [currently] needs to squeeze into one of these business models. There are other options in the world. As soon as you open your mind to for example, micropayments, you begin seeing all kinds of other opportunities as well.

Why publishers are brand building, with Ozone CEO Damon Reeve

JB: I’ve talked to other micropayment companies and they’ve viewed their centralised model as like when you were buying newspapers, where you’d go to an actual stand, and perhaps shop for your news from multiple sources all at once. The competition between different publishers was not the same as it is today, where you want your audience more exclusively and you want them constantly in all your verticals. Today, consumers want to consume news from lots of different places and can’t afford to pay for all of them.

I’m curious, though, for a place like Post, there hasn’t been a single alternative of a microblogging-type platform (of which you might get lumped in with) that has emerged post-Twitter. It strikes me that you need to have some sort of critical mass of audience to reach a high level of success. What do you see as the main challenge to get Post to that critical mass? How do you get a great deal of people signed up and paying and reading news?

NB: After Twitter, I don’t think there’s going to be one place where everyone’s at. I think a lot of the journalists will go to Bluesky, a lot of the athletes and celebrities will go to Threads, and the tech geeks will look to Mastodon. There will be different use cases for these platforms, so for us, ‘What is critical mass?’ is a hard thing for us to understand. We don’t actually know what it is, but one of the advantages of our model is that we don’t need to have every person on the platform. We want to be able to satisfy your news needs.

I think what you will find in the future is people using different platforms for different needs. TikTok did not destroy YouTube, it created something else. Now, you could argue they’re on a collision course and that at a certain point, everybody wants to offer everything, like what Snap and Instagram were, originally. But I think we’re heading in a direction that is the furthest from the idea of a super app as possible. Super apps work in China because China is a unique place; they haven’t worked outside of China because China is a unique place.

JB: You want to be the place for news and publishers. But you don’t have every single publisher in the world yet on Post. The big ones that you do have include The Boston Globe, The New Yorker, Reuters, and more. These are big global names, let alone big in the US, but I’m curious what it will take for more and more publishers to hop on. Especially as someone based in the UK, there’s some big publishers here. What have the conversations been like in trying to get more publishers to buy into your model?

NB: We are seeing a lot of UK publishers looking to the US. The Independent is on Post, as is The Mirror.

The way I think about it is there are three levels of publishers, let’s just take in the US market. At the top, there are the Big Three: The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. These are the monopolies. The current subscription model is working well for them—if you’ve got hundreds of millions of actives, 2% conversion [to subscription] can work. If you’ve got 20 million actives, 2% doesn’t pay the bills.

The way I think about it is there are three levels of publishers, let’s just take in the US market. At the top, there are the Big Three: The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. These are the monopolies. The current subscription model is working well for them—if you’ve got hundreds of millions of actives, 2% conversion [to subscription] can work. If you’ve got 20 million actives, 2% doesn’t pay the bills.

They’re big, and they’re getting bigger faster than the rest of the industry combined.

To put it into perspective, only 20% of Americans subscribe to any kind of newspaper, and of them, half, just 10%, subscribe to just one. The first one they subscribe to is usually one of those Big Three. So basically every other publisher knows they are competing with them, but The New York Times probably has more engineers than the rest of the industry combined. So, I don’t think the monopolies will ever come to our platform; I think they’re the ones that would say that we’re a competitor, because if we’re successful, they have a problem.

On the lowest level, you’ve got local news, which has been hit hardest. We haven’t launched our location features yet, which is why we haven’t brought on a lot of local outlets to this point, but one of the big things we’re working on is to be able to serve users news at a granular level based on their location. Once we get that, we have tremendous interest from the local publishers, so I’m not worried about that at all.

The third level is everyone in between, most of whom are trying to be mini New York Times. They try to give you everything, which also means they give you nothing unique. When you strip away what’s the same news being covered from all the outlets, what you’re left with is a very, very small percentage of original content. But that’s where all the value is.

What I think we’re going to see going forward is more specialty in these kind of mid-tier publishers. They need to be known for something that’s not just news. What is USA Today known for? What is CNN known for? The New Yorker, we know what it’s known for, it’s known for long-form content, even though a lot of what they do is still run-of-the-mill news. These publishers in the middle tier will need to start asking themselves: what are we? What’s unique about us?

JB: It sounds like you’re positioning Post as that fourth publisher that aggregates all other publishers against the Big Three in the US.

NB: Exactly. And, you know, I don’t think that the ‘standard news’ has that much value, but the unique pieces have tremendous value. It’s a small number from each publishers, but if you aggregate them together, you can get a very interesting experience. The same thing goes for creators and newsletter writers.

JB: Last question: you came from leading Waze, including after it was purchased by Google. Now you’re essentially getting into news publishing through a social platform. Reflecting on yourself very briefly, why did you make that change?

NB: I believe we have two existential challenges right now, as humanity. The first is climate change, and that I see as the hardware problem. Can we live here in the future physically? The second is, in my view, the rise of authoritarianism, which is a software problem. Is it going to be worth living here?

I’m not saying that social media is responsible for it, but it’s definitely an accelerator of the worst in society. I’ve been obsessing about this space for a long time, and I think we all have been complaining about it. At a certain point, I was like, you know what, we can’t just complain, I’ve got to try to do something. I don’t know if we’re going to succeed or not, but we have to try.

We can’t just give the public squares to the fanatics and assume that everything will work its way out. It won’t.