Windows to the soul: The compelling relationship between attention and profit

Opinion

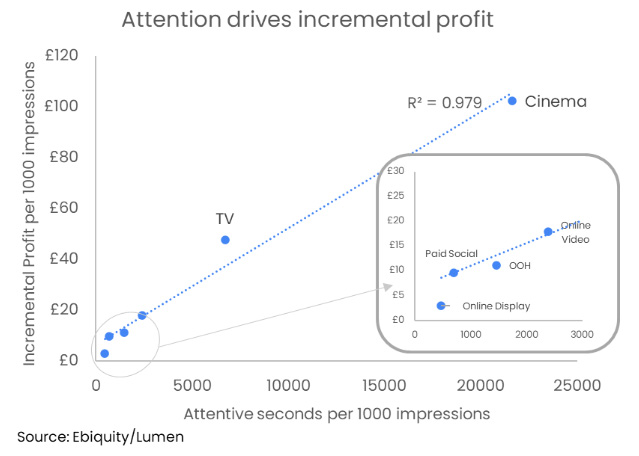

The latest research from Ebiquity and Lumen has shown that, on a basic level, we can probably use attention to predict profit. But it has also revealed something important about human desire.

The correlation is near perfect: the more attentive seconds a medium generates, the greater the incremental profit that is generated.

But the neatness of the fit actually begs more questions than it answers. What exactly is the meaning of our discovery?

The Ebiquity and Lumen datasets are both robust.

Ebiquity has mashed together two datasets — one about the incremental profit that ads in six kinds of media generate and the other about how much attention ads in each of those media channels tend to generate. The correlation between the two datasets has an R² (or coefficient determination) of 0.979 — 97.9% of the variation in the profit data is explained by the attention data.

Its “incremental profit per 1,000 impressions” calculations come from a meta-analysis of econometric models included within the Profit Ability 2 project. This took 141 econometric models from advertisers across 14 categories deploying over £1.8bn in adspend and looked at the long-term profit that was driven by ads in different media.

For instance, it found that £1 spent on online video advertising generated £3.86 in long-term profit. Given that it typically costs around £4.62 to buy 1,000 online ad impressions, the incremental profit per 1,000 online video impressions would be 3.86 x £4.62 = £17.83. Other media have different multipliers and different prices.

The Lumen dataset is also extensive. To date, we have collected attention data from over 700,000 individuals, measuring millions of ads and billions of eye movements. From this enormous database, we can construct average attention levels to ads in different media. We do this by calculating the chance that an ad will be seen at all and multiplying this by the time that it is likely to be seen for.

For instance, if you buy 1,000 online video ads, they might have a 47% chance of actually being looked at, for an average of 4.8 seconds each. So that’s 47% x 4.8 x 1,000 = 2,256 attentive seconds per 1,000 impressions (APM). As with the incremental profit calculations, other media will have different APM scores.

When you correlate the incremental profit per 1,000 scores with the attentive seconds per 1,000 scores, you get an almost perfect fit. The more attention your ads generate, the more profit you will make.

Close correlation

Now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. The underlying dataset may be large, but the datapoints we are playing with here are sparse.

The Profit Ability 2 analysis looked at a selected number of media and the contribution of the media as a whole, rather than investigating the specific contribution on TV ads shown on station A versus station B or format X versus format Y on the same social network. We know that there are great differences in attention within media — but we’ve only got six data points here.

We also know that there are great differences between campaigns: ads can be more or less effective depending on the size and mental availability of the brand, the ad responsiveness of the category and the quality of the creative. And 141 campaigns is a big number — but it’s not exactly Big Data.

But even with these provisos, we’re still left with a correlation of 0.979. I mean, that’s got to mean something.

Predicting profit

On a crudely commercial level, this probably means that you can use attention to predict profit.

In a perfect world, brands would use profit to predict profit: using instantly available econometric models so that recent performance could inform future budget allocation. But econometric models can take time to conduct and complete.

If attention data is a seamless proxy, why not use that as a leading indicator for scenario planning and forecasting?

The smart money is, of course, already doing this. Lumen data is embedded within the planning tools of five of the “big six” holding group media agencies. It’s used to power pre-bid buying algorithms across a variety of demand-side platforms. And it is used as an additional explanatory variable within many media mix model providers.

Measuring desire

However, there may be a deeper meaning to this data.

If the correlation between attention and profitability really is that tight, then we have learned something important about human attention and human desire.

Profit is the ultimate measure of desire: if lots of people want your product and are prepared to pay for it, you will make more profit, whatever the complexities and vicissitudes of a competitive market. Advertising plays an important role in manufacturing and directing this desire.

What we have shown here is that, at least for advertising, attention and desire are coterminous. We direct our attention to our heart’s desire. The eyes truly are the windows to the soul. Perhaps we need a new word for the eye-tracking technology that companies like Lumen have developed.

The word “telescope” fuses the Greek words tele (at a distance) with skopos (to see). The microscope helps us see things that are very small (from mikros). What should we call a device that helps us see desire? The himeroscope — the yearning glass? The epithumiscope — the craving machine? The erotoscope?

We have known about the relationship between attention and performance metrics for some time. Havas has recently taught us about the relationship between attention and memory. Now, Ebiquity has filled in the final piece of the puzzle by showing the relationship between attention and profit.

But as we have been filling in the pieces of the puzzle of attention and outcomes, we are beginning to realise that we are revealing a much bigger picture.

Mike Follett is global CEO of Lumen and one of the media industry’s leading experts on attention measurement and effectiveness

Mike Follett is global CEO of Lumen and one of the media industry’s leading experts on attention measurement and effectiveness