Adtech startup Into-It wants to replace banner ads with something better

The Media Leader Interview

Into-It founder Lee Henshaw explains why his Chrome extension, which replaces banner ads with personalised notifications about musical artists, would be a boost for publishers — and the product’s wider applications.

“Display advertising is broken.”

Lee Henshaw, founder of adtech startup Into-It, wants to transform standard banner ads on websites into personalised notifications related to the music industry.

“[Display’s] future rests on a knife’s edge,” Henshaw tells The Media Leader over video call. “For people who are buying it, it’s a classic market for lemons, full of information asymmetry. It’s terrible for publishers; the inventory has been devalued, defunded. And people hate it. [American blogger] Doc Searls describes ad-blocking as the biggest consumer boycott ever“.

In search of a more consumer- and publisher-friendly solution to digital advertising, Henshaw founded Into-It as a “side hustle” in December 2020 amid the Covid-19 pandemic. He had previously founded and run Silence Media, a specialist in digital personalisation strategy, media optimisation and creative execution, which was acquired by independent media sales house Canopy Media in May 2023.

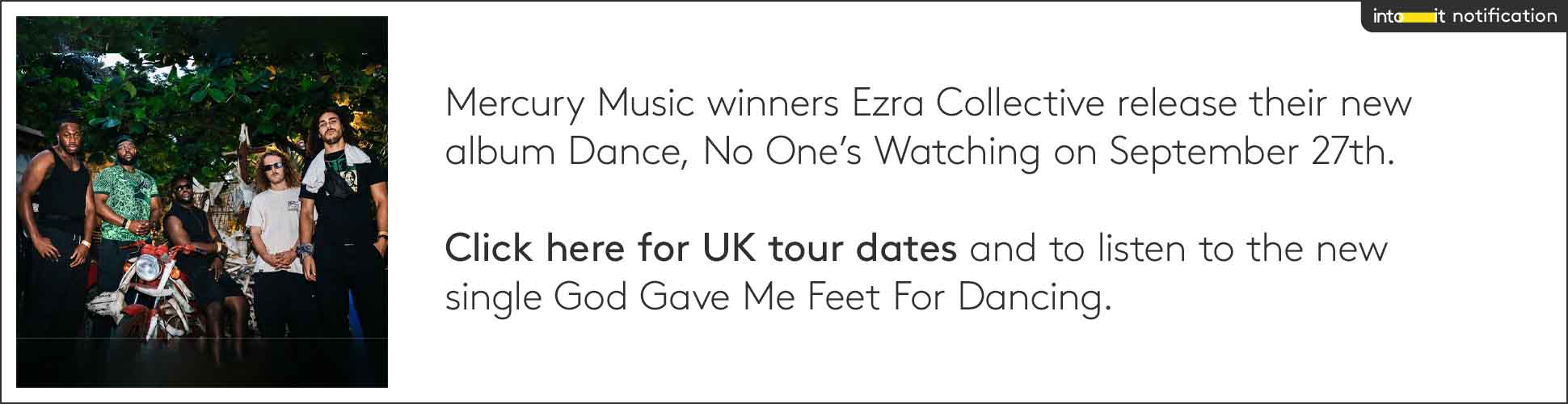

Into-It currently has patent pending on its software and is in the midst of a third investment round. Henshaw tells The Media Leader that Into-It will “hopefully do a Series A round early next year” following the launch of a Google Chrome browser extension that will replace banner ads on certain publisher websites with what he calls “notifications” related to the music industry.

The extension is slated for a September UK launch, and if Into-it secures additional funding, Henshaw would use it to help launch the tool in the US, as well as develop it on browsers other than Chrome. In addition, he hopes to eventually expand beyond the music industry to include other entertainment sectors, including films, video games and theatre.

Users who download the extension will be able to list the musical artists they’re into, and when they go to a publisher website Into-It has partnered with, instead of seeing classic ad banners, they will see information related to relevant musical artists, such as latest releases, upcoming concerts or merchandise sales.

Into-It’s advisory board includes Lucky Generals creative founder Danny Brooke-Taylor, The Barber Shop founder Dino Myers-Lamptey and entrepreneur (and partner of Doc Searls) Joyce Searls.

Potential benefits to labels and publishers

The Media Leader understands that publishers were invited to take part in a price survey last month to help gauge the economic value of the product.

The Association of Online Publishers (AOP), the trade body representing digital publishers, recommended its members participate in the survey as a way to test Into-It’s technology and contribute feedback on its pricing model.

A similar survey is concurrently under way with record labels and the results from both will be used to establish Into-It’s price structure.

“Into-it is an exciting and interesting proposition for publishers looking for a credible audience monetisation solution for the post-third-party cookie world,” says AOP managing director Richard Reeves. “The potential benefit of this technology for our members is that they can charge more money for serving notifications than they do for banner ads, as the price survey will establish.

“This collegiate approach to pricing is very encouraging and I hope others in the industry will follow this type of methodology — collaborating with digital publishers upfront to establish best practice for all. I’d therefore urge publishers to take the opportunity to directly feed into this discussion.”

The Independent’s CEO eyes publisher partnerships beyond BuzzFeed

Henshaw declines to name specific music labels and publishers that are currently testing Into-It’s solution, but music clients include “all the major record labels and indies, concert promoters and merch companies”. A beta test in 2022 included the likes of EMI, Columbia, Domino and Koko.

“We’re hearing from our record company clients that they’re ready to move budget from social to online display — something you don’t hear often,” explains Henshaw. “This means online publishers working with Into-it will have a better dataset than on social channels.”

Meanwhile, Henshaw is approaching publishers and is most interested in providing his music clients with audiences who index heavily in the 18-34-year-old demographic, which is understood to be the prime age range for new music discovery.

Henshaw argues: “The benefit to music clients is better communications. The benefit to publishers are clear business benefits too. It’s about getting a higher yield from those pages.”

Moving towards an ‘intention economy’

There are also potential benefits to consumers, many of whom have been turned off by display advertising over the years and have installed ad-blockers to remove unwanted clutter and pop-ups.

According to online advertising company Blockthrough, the number of ad-block users grew over the past decade to exceed 800m globally across PC and mobile. With Into-It, Henshaw is betting that by directly engaging music fans about their preferences, “we ensure that notifications are relevant and welcome, offering a respectful and effective alternative to online advertising”.

Indeed, he is at pains to draw a distinction between standard ad solutions and Into-It, as he views advertising as “something that is pushed upon you”, whereas Into-It’s “notifications are pulled in”, with users opting to install the tool and having direct input on the type of content delivered to them.

The philosophy comes from a desire to move away from the dominant digital attention economy and towards the “intention economy”, a concept coined by Doc Searls that places focus on buyers of goods rather than sellers.

He has referred to Into-It’s work as “magnetic messaging” that will be “expected and welcomed”, adding: “This is not advertising, even though incumbent advertising mechanisms are involved. What’s unique and new here is a pull mechanism, not yet another form of push and not one that requires tracking or guesswork.”

Still, it will be a challenge to attract users, both in making them aware of the product and convincing them to download it and supply it with information. Henshaw admits as much and says his team is working on developing a marketing push, calling it “the million-dollar question”. But he hopes providing the market with what he believes is an improvement on the digital ad experience will catch on, much like music streamers did.

“I was there in the 90s. I was working in the music industry,” says Henshaw. “The arrival of streaming in the 00s and into the 10s — that was the thing that brought illegal downloaders in from the cold, because you just didn’t need to do it any more. There was just no point; you could get everything anyway for a tiny subscription fee.

“I hope that people who are using ad-blockers in certain circumstances — and I understand why; why wouldn’t you when the experience is so horrific — will look at something like this and think: ‘That’s great. That’s much better.'”