'There is no Plan B': why 'Madison Avenue Manslaughter' author Michael Farmer says agency groups will break up

The Media Leader interview

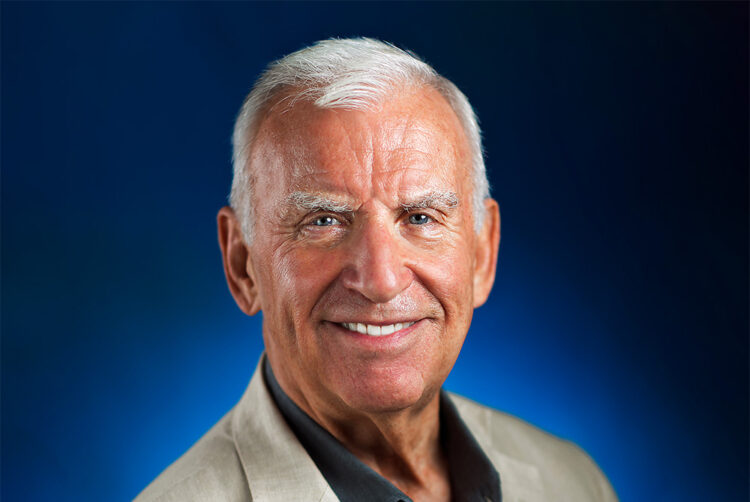

Michael Farmer is writing a sequel chronicling one ad agency’s attempt to transform itself. But why does he think media and advertising holding companies are holding agencies back and will ultimately get broken up?

“Agencies, both old and new, should take note of Michael’s focus on scopes of work and its continuous examination and re-evaluation. It’s a critical factor in agency development or even survival. Listen to what Michael says.”

That quote, by Sir Martin Sorrell, ends his foreword of the third edition of Michael’s Farmer’s award-winning Madison Avenue Manslaughter, a book that caused ripples of mirth or horror throughout the advertising industry, depending on which company you work for.

“What Michael says” essentially boils down to an insight he learned early on as a consultant for ad agencies while at Bain: they seem unable to carefully define and stick to scopes of work. This creates a culture in which agencies service advertiser accounts by essentially being a concierge: whatever the client wants, the client gets.

But, nearly seven years after Madison Avenue Manslaughter was first published, has anything changed?

Speaking to The Media Leader from his home in Madison, Connecticut, Farmer instinctively laughs at the question—his blue eyes darting towards the sky, as if to say, “are you out of your mind, son?”

Farmer is currently writing a sequel: Madison Avenue Makeover, in which he has collaborated with a well-known agency CEO who is making a concerted effort to transform his agency so as to avoid the ‘slaughter’.

But more on that later.

Here is an edited transcript of The Media Leader’s conversation with Farmer.

Omar Oakes: Michael, thanks for taking the time to chat. Where are you calling from, where is home for you?

Michael Farmer: I live outside of New York in Connecticut, Madison, Connecticut, which is on the shore. It’s about a two hour commute by train into New York, but a very easy one, which I do a couple times a week. I’ve lived out here about seven years, after 35 years of living in different cities around the world. It’s more peaceful and it was a lovely place to be during Covid lockdowns.

But it’s funny, I spent nearly 20 years in London in the 80s and 90s. When I ran Bain in Germany, France, and then the UK, I pretty much lived there for 15 years and raised my daughter there. And then we moved to New York, because where are you going to go after London?

Oakes: I very much enjoyed your book, which I read over Christmastime after a number of people in the industry had recommended it to me. Do you think much has changed since you first published it in 2015?

Farmer: The third edition has got some significant additions that dealt with the media meltdown that occurred in about 2017, when it revealed that media companies were, instead of just acting as agents for their clients, they were using the client money to make their own bets and to do some arbitrage on media costs, particularly in programmatic, which is disgraceful.

But what are you going to do when fees have been coming down for 30 years, and the workloads go up? It just encourages people to think of radical ways of making money to please the holding company.

I just see media clients wanting more and more fragmentation. By doing more and more campaigns, they’re trying to find something that works. And they’re not going about it systematically by saying, ‘let’s sit down together and do a whole bunch of analysis on what we’ve spent in the past and what we got for it’.

Michael Farmer

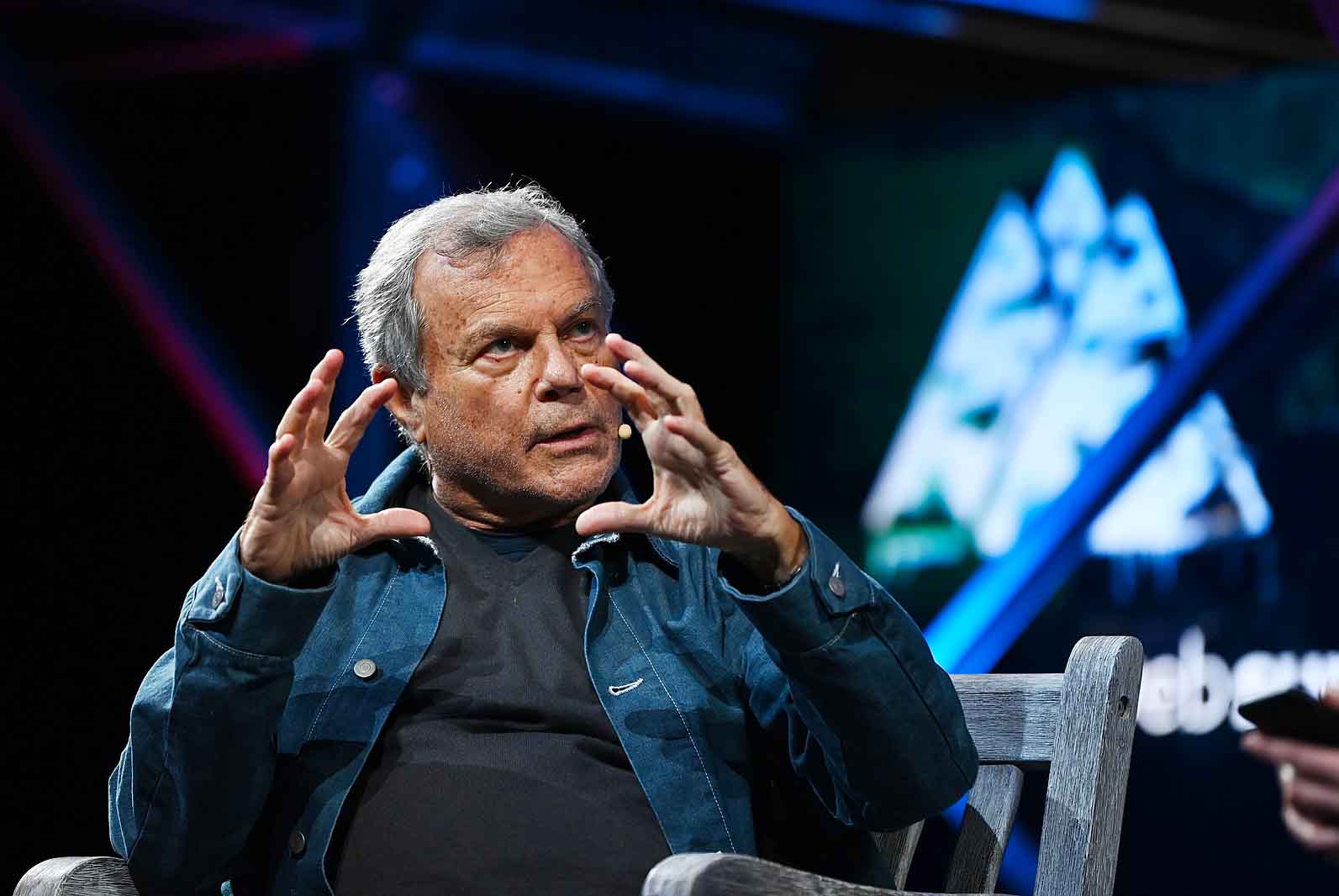

The second thing is, for the third edition, I was able to get Martin Sorrell to write a chapter. It’s funny that this has received almost no publicity, but what he wrote is extremely revealing about what he was trying to accomplish.

He resigned [from WPP] in April 2018 and I was able to spend, oh, an hour and a half interviewing him in September or October. WPP was already behind him and S4 Capital had just started.

I asked him to reflect on all the challenges he had during his 30 years at WPP and he suggests that the holding companies don’t really have a strategy of making the numbers work. They don’t have a viable long term strategy so that they are sustainably strong and relevant. Every year, they squeezed their agencies a little harder to make the margins. And I think they’ve run out of headroom. They’ve gotten very good at client development, but they’ve also gotten very good at losing clients at exactly the same rate.

So, I mean, net, they’re not growing, and every time they add something it is under worse conditions than what they just lost, and they make up for that by putting the squeeze on the companies they own. So there you go. It’s not a viable strategy and it will, at some point have consequences. But who knows when?

Oakes: You mentioned after the the media meltdown five or so years ago—what’s your reflection on it now? There are still lots of questions over how transparent the relationship is on the media side between the agencies and clients. Has anything changed on that front?

Farmer: I don’t think it has. There was a flurry of activity and developing greater transparency. A lot of clients took programmatic in house. There has been a lot of reviews, big, big, big, media reviews, and I think that procurement is still bashing fees. If there’s a big holding company relationship on media, then there are massive economies of scale: if a mobile company like T-Mobile spends between $1bn-$2bn a year on media and say ‘if we’re going to give that to a holding company, we expect something for it, in terms of low-cost planning and buying’.

The thing is, that pressure, that ignores something else that’s going on, which is the more you fragment the channels in which you spend, the more it is a series of little relationships.

I’m working with a media agency that has asked us to analyse 35 of their global clients, which probably adds up to something like 60 or 70 separate scopes of work. And we are trying to understand the complexity of those relationships by virtue of the following things: how fragmented is the spend among channels? How many campaigns are they having to support within each channel? How many ROI reports are they having to generate to keep track of that?

What’s happened with the fragmentation of media, and this ‘all you can eat’ buffet for clients, is that they can get the media agencies to do anything just because they want the revenue. So they’re getting more channels, more planning, more buying, more campaigns, more briefings, which adds more to the budget approval process. But all of that ROI and that complexity is not being reflected in the fees. The major media agencies are sucking wind because of complexity, but they desperately want the revenue because that’s what they need to hold up their budgets.

So I don’t see any dialogue about the transparency issues anymore. I just see media clients wanting more and more fragmentation. By doing more and more campaigns, they’re trying to find something that works. And they’re not going about it systematically by saying, ‘let’s sit down together and do a whole bunch of analysis on what we’ve spent in the past and what we got for it’. They’re looking for ROIs in every individual campaign within every individual channel, as opposed to figuring out what works.

And, you know, I think that the analysis that goes on for the ROI stuff is not particularly good. They have to do so much of it and they have to do it so quickly. Even though the media agencies don’t even have the resources to do analytics. If you think about it, their whole budgets are consumed with paying for media planners and media buyers… There are separate analysts that are needed to do all the data analysis that clients are asking for, but there’s no budget for those folks.

And if you’ve got to buy a ton of media across a lot of channels for a lot of campaigns, you are not going to scrimp on media planners and buyers and you are going to scrimp on analysts and strategists and even client handlers

Oakes: And where do you see this going? Should we expect to hear more to happen internally from these holding companies in terms of restructures and doing things differently? Where’s this all heading?

Farmer: You’ve got declining prices, you’ve got growing complexity and costs, and underperforming clients who are trying to take stuff in-house.

I think it is headed in a direction where the holding companies end up being broken up. I don’t see the value added by a publicly-owned holding company. Let’s go back to the WPP example, and what Martin [Sorrell, pictured, below] talked about: Martin kicked this all off in 1986, with his purchase of J. Walter Thompson, which was earning (in an all-commission era) a 4% margin.

A couple years later, he bought Ogilvy that was earning on 8% margin. And Martin said, ‘I know the reason they are making that margin—they’re completely overstaffed for everything they need. They are putting two, three and four creative teams on everything.’ He knew that from spending 15 years at Saatchi as a finance director. So he had a very clear strategy: you buy a high-cost underperforming company, and you take the excess costs out of it, drive up their margins, and drive up your own and drive up your share price, which makes it easier for you to make other acquisitions at lower cost to your earnings per share.

From 1986 to 2005 the only strategy was for the holding companies to take out those excess costs. And, by the way, clients were doing the same thing once they shifted from commission to fee. So they were working jointly with each other; the holding company wasn’t screaming about the lower fees, because they knew there were extra resources to be taken out.

Now, in 2005, all the extra resources were gone. WPP needed a Plan B. And Martin didn’t have a Plan B; he never had a Plan B for WPP. Holding company relationships were not a Plan B to add value. It was just dealing with the fact that the agencies themselves have not diversified quickly enough into digital and social—that was the genesis.

So he had to, in order to hang on to clients, create holding company relationships. And that’s the only thing that exists today, where Publicis Groupe just wants to be known as Publicis—“The Power of One”—and you never hear anything about Leo Burnett or Saatchi & Saatchi or Publicis USA. Those are gone, those brands hardly exist.

If you look at the investment reports, the analyses of the holding companies, they still don’t know how holding companies make money

Michael Farmer

And with WPP it’s kind of the same thing: you don’t hear very much about Grey, which has now been merged with AKQA and JWT is now Wunderman Thompson. Ogilvy is still Ogilvy, but you don’t hear much about the brands, you hear about the holding company relationships.

Martin did not set the tone by developing a Plan B. That’s why he’s out, I think, because in 2018 their shares dropped by 30% when he was still in. Yes, there were other things that they were unhappy with. But, basically, he didn’t have a new strategy. I don’t think Mark [Read, current WPP CEO] does either.

And who does among the holding companies? They’re all still trying to make margin and squeezing the agencies, they’re still doing it like it’s pre-2004. The only thing they’re adding to is holding company relationships. But none of them are growing at an extraordinary rate. They’re just swapping out one relationship for another. I don’t see how they can continue to squeeze agencies and raise dividends, which they’ve all done, and do share buybacks.

Oakes: But surely the investment community at the big banks can see what you’re seeing?

Farmer: If you look at the investment reports, the analyses of the holding companies, they still don’t know how holding companies make money and how fragile they are with respect to the expertise of the resources and the seniority of the [agency talent]. Look, the average salary at a holding company agency might be around $110,000. But Bain, BCG, McKinsey, Accenture, Deloitte… they hire people out of business school at double that rate! The talent is not coming to the industry, what talent is there has gone out and is competing as freelance, and the people that stay are junior. I just don’t think the analysts realise just exactly how fragile the staffing situation is of the agencies. Yeah. And then they just worry about whether the agencies will grow at 2% or 3% and whether they’ll continue to deliver 16 or 17% margins.

Oakes: And then it became particularly acute during the pandemic, when agencies made layoffs. But when the industry rebounded, they tried to hire back lots of people and they’ve really struggled. And what you’re seeing is the middle has been hollowed out—you’ve got highly paid executives at the top who are still there, you got the junior people, as you say, but all those middle people are gone. And that’s really where they’re they’re suffering.

Farmer: Oh, definitely. I’ve done over 1,000 diagnoses of scopes of work [at agencies]. I get to see the seniority and the salaries of the people staffing these big clients. If you take a typical relationship, the average salary cost is $100,000 per head. And the client might be paying $220,000 for that full-time equivalent—a 2.2 multiple. So the billing rate is $220/hour times, let’s say, 1,800 hours. Well, consulting firms are getting four times that! They’re taking taking $100,000 per person and billing it out at $500,000 a year. And that’s the most junior people that they have—not the average.

Oakes: But hold on, for a number of years, we’ve been looking at Accenture, Deloitte, Bain, acquire different ad agencies of different sizes and look to kind of do more marketing services. Everyone looked at them and thought, ‘oh, these guys are going to come to eat the holding companies’ lunch’, but it hasn’t quite happened that way. Why do you think that is?

Farmer: For one thing, I think if you take Accenture, I don’t imagine that they have significantly improved the billing rates of their agencies. I don’t have any information on that, I’ve have never worked with Droga5 or any of the agencies that Accenture or Deloitte have acquired, but I suspect that they have done more to continue the length of the relationship.

In other words, if they are selling their way in by helping clients to digitalise their offer, to do ecommerce, improve their systems, or be more customer friendly… that work is fundamentally strategic and operational. It’s the kind of stuff they’ve always done, even when [Accenture] was Andersen Consulting.

I think they bought the ad agencies so that they can continue the right relationship and then do the media planning and the media buying. So that it’s an integrated full service offer. What they’re offering is a really strong front end that the agencies cannot replicate. I don’t think they’re necessarily eating the lunch of the holding company agencies. I think they’re another competitor that they have to worry about who may have a better story. And the better story is, ‘we’re here to help you improve your overall performance by helping you digitalize in a digital world’. You don’t see that coming out of Omnicom, Interpublic, or WPP. And even if the talk is there, they’re not backing it up with the resources.

I took a look at WPP’s various websites and LinkedIn to find out: who are the WPP holding company people in North America? What do they do? Because I’ve had to work with a number of them. For example, I was hired by a major FMCG company to examine the nature of their relationship with one of the big holding companies to see if that could be streamlined in some way. So I got to work with the holding company individuals and the agencies that were actually doing the work. It looked to me like the holding company people were not adding much value because the agencies don’t really pay a lot of attention to them.

The holding companies should take a billion right off [and say] ‘We need to completely revamp our talent structure, our mission, our way of thinking about why we’re doing what we’re doing.’

The funny thing is that if a Mark Read did it or John Wren did it, I think their share price would be rewarded.

Michael Farmer

But in any case, I identified through LinkedIn, and websites that WPP had about 79 staff people at the holding company level in North America. And then 80% of them had job titles that suggested they helped “develop clients”. Either they were industry experts or they got involved in pitches. But, believe me, they were not there to help agencies improve their operations.

I’ve even heard of some cases where a holding company in a media pitch offered free creative to the client. Those kinds of deals are just insane if you’re trying to improve agency operations. So I don’t see the agencies working with the agencies to prove their operations, I see the holding companies desperate to develop more business. The whole game has been about business development, business development, business development at the agency level and at the holding company level. And the hope that volume will make up for terrible fees.

Oakes: And now I understand you’re in the middle of writing a new book. What’s it about?

Farmer: Yes, exactly a year ago, I received a call out of the blue from Mat Baxter [CEO of Huge, a global digital creative agency, part of IPG]. Mat was CEO of Initiative [IPG media agency]. And I had been working with Initiative, but not under his sponsorship. In fact, I had never met Mat directly. We have some email correspondence in before Covid and he any sort fobbed me off on Amy Armstrong, who is his North American CEO—a fabulous person. And I did work for her.

Then, out of the blue, he got appointed in 2021 as CEO of Huge and I sent him a note congratulating him. Two months later he called to say, ‘I’ve got a project for you. I want you to be a fly on the wall and write an independent book about our transformation’.

I thought, ‘man, where have you been for 30 years of my life? I’ve spent 30 years in the industry and I’ve worked with nearly every CEO of every major agency, and you’re the first to say I want to do something about the horrible situation’.

So I started interviewing Mat and all of his management team and participating in every management meeting, which I’ve been doing for the last year. And I now have something like 534 pages of transcripts from all my interviews and a lot more bought more material than I can deal with. And I started writing the book a couple of weeks ago. So I’m about 5,000 words into a 50,000-word book. He is insistent that it be my book and covers the good, the bad, and the ugly, even stuff he might be doing that doesn’t appear to be right.

It’s going to be called Madison Avenue Makeover: Will Mat Baxter’s Transformation of Huge Set a Strategy for Ad Agencies?

It’s pretty radical, what he’s doing over there. There isn’t an aspect of their operations that he isn’t changing. He doesn’t want to be called an agency anymore. He wants to work with clients in long-term relationships to improve their top-line growth and competitiveness with a product line that has been completely overhauled to do that.

For example, he has 12 offices now in Huge, all of them profit centres, just like every other agency.

Oakes: But he still has to deliver what IPG asks of him in terms of hitting the numbers. Is he doing this transformation with help from IPG or despite IPG?

Huge is small relative to McCann or FCB. He has the freedom to experiment and he wouldn’t have been selected for the job by Michael Roth or Philippe [Krakowsky] if they didn’t expect him to stir things up. That’s his reputation. That’s what he’s done for 20 years in media. It’s the adage of redesigning the aircraft when it’s in the air. He’s got to balance both working with the old Huge, and the existing clients on existing programmes and not upsetting them, while he’s trying to overturn things in terms of the culture, the product line, and everything else and get new clients that he can add to it.

And, bear in mind, they wouldn’t put him in charge of McCann to do the same thing on an experimental basis, because they have too much to lose with McCann.

Oakes: What about the newer companies that have come on the scene? So you know, we’ve talked a lot about S4 Capital, you’ve got others like David Jones, who used to run Havas, now running The Brandtech Group. Do you see that these companies are doing anything particularly different and might stand a better chance of having better relationships long term?

Farmer: I have no inside knowledge —only what I read in the press. But I’ve known Martin [Sorrell] for a long time. You know something about S4 Capital? Martin is a super salesman for business. He does not get enough credit for being maybe the best salesman for relationships in the entire industry and he has brought a lot of business to S4 Capital.

I don’t think [Media-Monks, S4 Capital’s agency group] is doing anything very different, but they’re integrating everything and he’s out there pitching. That’s what he does best. As far as David Jones is concerned, I don’t really know. I do know that there are a lot of smart ex-agency people out pitching at the strategic end of the value chain. In other words, they’re pitching to CMOs: ‘we can help you get a better understanding of your situation and help you come up with better macro marketing ideas that you can pass on to your media agency and your creative agency’.

Oakes: As a concluding thought, you’ve had critical things to say about both the marketers and advertisers on the buy-side, as well as saying the agencies haven’t changed in the way that they needed to. So who’s more to blame?

Farmer: Public ownership and the concept of shareholder value has corrupted agencies. There was a time when agencies were still pretty fat and digital/social were just coming in. That was a time when a Mat Baxter-type would have said, ‘I don’t like what I see coming down the road. I think we have to make some fundamental changes in the way we’re paid.’

There was a time when those very agencies should have embraced new technology aggressively. But there was a complacency and maybe a laziness, and the fact that they were paid way too much money for making their numbers. That that has continued since 2005. And now who wants to give that up? For what might appear to be Mission: Impossible?

The holding companies should take a billion right off, set a billion-dollar reserve to say, ‘we’re gonna take our reserve against profits because we need a reprieve from the quarterly earnings pressure. We need to completely revamp our talent structure, our mission, our way of thinking about why we’re doing what we’re doing.

The funny thing is that if a Mark Read did it or [Omnicom CEO] John Wren did it, I think their share price would be rewarded. It would educate the City to what the problem is.

Oakes: The question I’ve always asked myself is about the major investors into these public companies — where is the accountability? You talk about shareholder value, but what about actually calling on leadership to do what needs to be done to secure the long-term future of these companies? I never see it. Even though, if you look up who are all the major institutional investors into all of these companies, it’s the same names that keep cropping up. They’ve got stakes in all of them.

Farmer: They’re tactical and non-strategic investors. They’re not Warren Buffett. If you take a look at the boards, the boards are not strong boards. They’re ancient. I don’t think the boards are asking the right questions. It’s a disaster in the making. But if public ownership is the issue, and the large amounts of money are the issue, then the disruption will be that public ownership ceases in some way. And that’s either by private equity coming in and saying, ‘hey, there’s a big opportunity, let’s buy them when things look bad and take them private, turn them around, and flog them in five years.’ That could happen.