Play it again, Sam: Ads need repetition to work

Opinion

So we recently found that it’s the sum, not the parts, that drives results when it comes to attention. But what about frequency? Andrew Ehrenberg, Erik du Plessis and toddlers all teach us something here.

One of the key learnings from the Havas/Lumen/Brand Metrics attention-to-intention research is the power of aggregate attention time in driving business results. The more people look at an ad, the more likely they are to remember the brand or consider it for purchase or, indeed, intend to purchase it.

Crucially, you can achieve the benefit of “more attention” by aggregating lots of little glimpses across multiple ads into a greater whole, rather than relying on one big uninterrupted chunk of attention time. It’s the sum, rather than the parts, that drives results.

This sounds pretty uncontroversial to most normal people, but it’s a topic of much contention for many marketers because it relates to the thorny issue of advertising frequency.

To massively — but, I hope, helpfully — simplify the issue, we can split the protagonists into two camps: Team Ehrenberg and Team du Plessis.

This head-to-head fight does neither man justice — the thinking of each was far more nuanced than what will be presented here and both were kind, generous souls who sought concord rather than conflict.

But marketers love a scrap, so here goes.

Team Ehrenberg: Reach over frequency

Andrew Ehrenberg was a statistician and what we would now call “marketing scientist” with a contrarian streak.

Andrew Ehrenberg was a statistician and what we would now call “marketing scientist” with a contrarian streak.

He noticed that many advertisers were deliberately buying TV campaigns designed to reach the same people time and again. When asked why they were doing this, media planners would say they had to serve ads weekly to influence people’s weekly buying habits; or to build loyalty; or to reach the “heavy buyers” who really delivered most of the value.

It’s easier to keep an existing customer than win a new one, went the accepted orthodoxy.

Ehrenberg thought that such folk wisdom was wrong on (at least) two counts. First, with mass broadcast media like TV in the 20th century, it was very hard to construct a media plan that will reach and influence your loyalists at the exclusion of non-loyalists. You may want to “find your tribe”, but reaching them is very tough.

Secondly, your “tribe” probably doesn’t exist. In most well-established and properly competitive markets, most people buy most brands in the category. You might like Coca-Cola, but you’ll accept Pepsi, especially if it’s on offer.

When you think about it, it’s slightly absurd to think that people are “loyal” to a yogurt or a cat food. Given the choice of spending money reaching a small group of “pseudo-loyalists” repeatedly or introducing a brand to the (much) larger group of light buyers, Ehrenberg advised us to go for reach over frequency every time.

Team du Plessis: Repetition is necessary

Erik du Plessis, the great South African TV researcher, was much more respectful of the wisdom of the crowd. No matter what media planners said they were doing (which would often pay lip service to Ehrenberg’s insights), they were, in fact, buying 3+ coverage as standard. And they were getting good results.

Erik du Plessis, the great South African TV researcher, was much more respectful of the wisdom of the crowd. No matter what media planners said they were doing (which would often pay lip service to Ehrenberg’s insights), they were, in fact, buying 3+ coverage as standard. And they were getting good results.

Du Plessis set out to understand why this might be the case. A behavioural economist as much as a classical economist, he would happily admit that most media planners bought 3+ coverage did what they thought other media planners did. They were uncritically following the herd.

But someone had to lead that herd. And so du Plessis conducted hundreds of experiments with the most forward-looking South African advertisers during the exciting years of post-Apartheid reconstruction.

As he details in The Advertised Mind (2005), repetition is necessary to create memories. And because people don’t buy from strangers, memories are required to drive business results. Balancing cost and reach, it seemed that 3+ coverage was the “Goldilocks” number to drive business results.

To make his case, du Plessis drew on the vast AdTrack database of over 30,000 TV ads, linked to questionnaire and sales uplift data, and combined it with a kaleidoscopic series of perspectives drawn from educational practice, evolutionary theory and the deep wisdom of Zulu miners. It remains the best book written about advertising published in the last 20 years.

Opportunity vs guarantee

So who is right? Reach everyone once or try to repeat your message to create a memory and drive a sale?

It’s here that the attention-to-intention data from Havas, Lumen and Brand Metrics provides an interesting angle, because it shows that advertisers have to buy at least 3+ frequency — so that they can achieve 1+ reach!

As is well-known by now, people are very good at ignoring advertising. You can serve ads to people, but that doesn’t mean they’ll eat them up. Advertisers have to realise that opportunity-to-see numbers mean just that — an opportunity to see an ad, not a guarantee that they will see it.

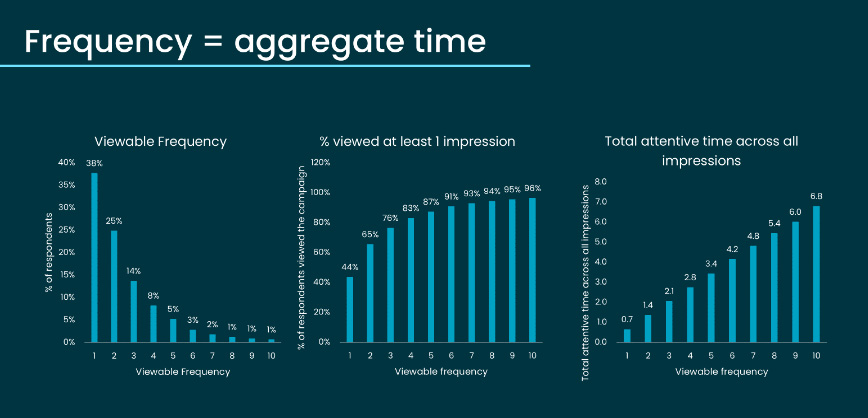

This means that just because you have reached the screen doesn’t mean you have reached your audience. Analysis of over 9,000 digital display campaigns and over 5.6m viewable impressions suggests that, to be sure that someone actually looks at your ad, you need to give them multiple opportunities to see it.

It looks like you have to follow du Plessis’ advice to achieve Ehrenberg’s target. Perhaps they are both right?

Repeating a message

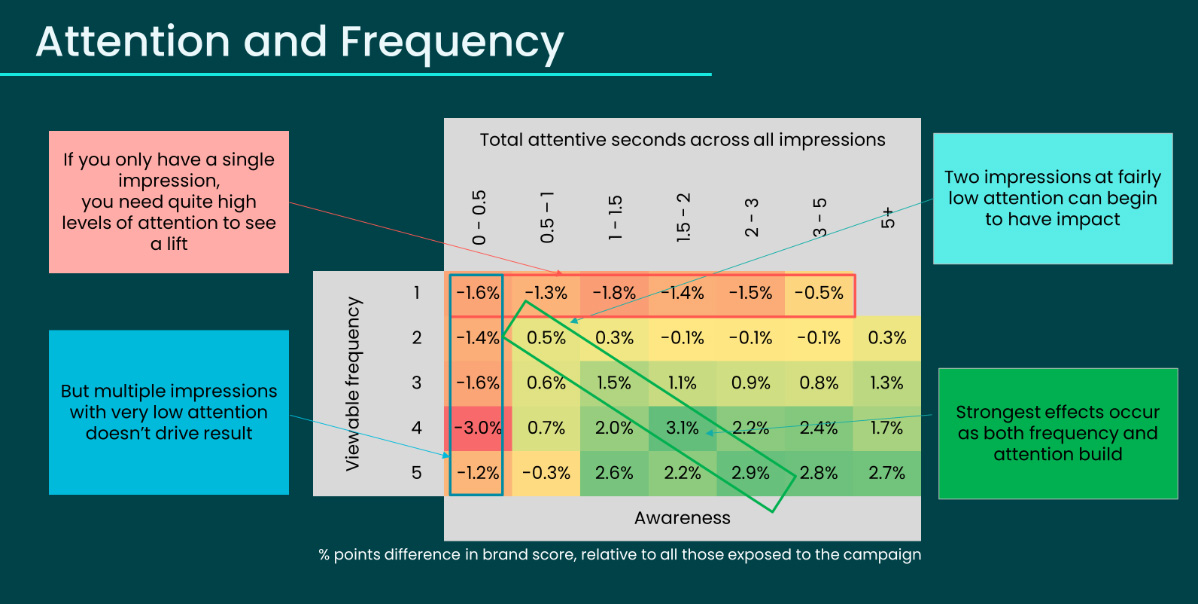

But analysis of the brand-lift questionnaire data tilts the debate in favour of du Plessis. Not only do you need frequency to achieve reach, but you also need frequency to build memories.

Havas has found that advertisers need to achieve relatively long lengths of attention time to move the needle when it comes to improving awareness, consideration, preference and purchase intent. This could be achieved by a single long blast of attention to a single ad or by multiple short bursts of engagement to a sequence of them — as we discussed in a previous article.

Of the two strategies, the Brand Metrics data suggests that the multiple-exposure approach is often more effective at building memories than the one-and-done technique. Getting people to look at a message three or four times quickly appears to improve metrics like awareness, consideration and preference more effectively than engaging them via a single, longer-attention session.

Why might this be? This is the sort of question that flummoxes your average ad man, but is easily answered by a primary school teacher or a parent or anyone who has to communicate with or educate someone who isn’t that interested in what you are telling them.

Of course you need to repeat a message to get someone to remember or act on it — and if you don’t believe me, read chapter three of The Advertised Mind.

Advertisers and the agencies that represent them have far more to learn from the attention patterns of a distracted toddler than the idealised concentration of mythical “brand loyalists”. This canard of “high-attention heavy buyers” is the true target of Ehrenberg’s ire. Empiricist that he was, I am sure that he would have been fascinated by the Havas data, especially once we publish our findings on video advertising.

And I am sure that he would have been able to build this phenomenon into his theory. As John Maynard Keynes, another great practical economist, said: “When the facts change, I change my mind — what do you do, sir?”

Mike Follett is global CEO of Lumen and one of the media industry’s leading experts on attention measurement and effectiveness

Mike Follett is global CEO of Lumen and one of the media industry’s leading experts on attention measurement and effectiveness