Opinion

Just as the advertising sector seems to doubt its ability to make impact, there are creative activists harnessing those very skills to create a counternarrative.

I recently saw a Tube card that stopped me in my tracks.

I had just been to the inaugural lecture of Professor Anne Karpf at the London Metropolitan University. Entitled She Loved this Place: Memorial Benches as Life Writing and Life Siting, it was a fascinating exploration of a uniquely Anglo-Saxon form of remembering people. Using predominantly wooden benches to provide communities with restful public seating, whilst also writing inscriptions to reveal a snippet of someone’s personal story.

Far from fading in popularity in our digital age, they are apparently increasingly sought after as a way of marking a life. The placement of such writing in very particular places, to quietly celebrate seemingly undistinguished lives, invites the general public to bear witness to bonds that would otherwise remain private.

Like all forms of writing there are a wide range of approaches: from the formulaic, “In loving memory of a person sorely missed” type, to the more subversive.

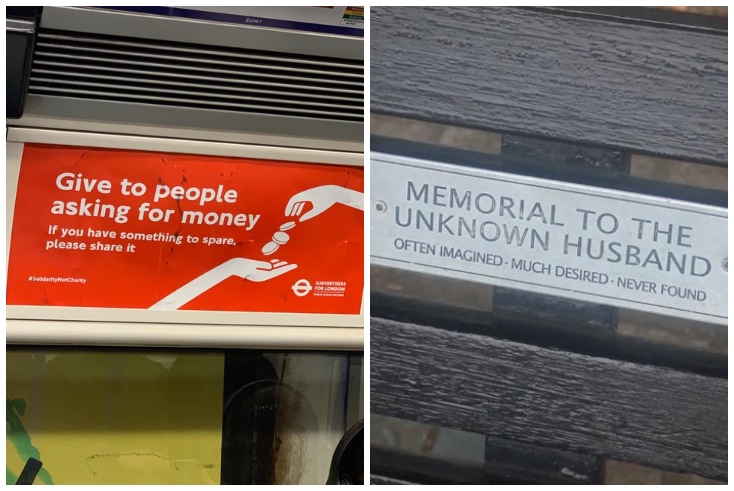

My favourite in that subversive genre is the plaque which appeared on the Queens Walk in London and read, ‘THE MEMORIAL TO THE UNKNOWN HUSBAND. OFTEN IMAGINED. MUCH DESIRED. NEVER FOUND.’ A sharp bit of writing using all the established conventions of memorials simply to make us laugh. The author is unknown and their motivation remains mysterious but their wit certainly makes an impact which has travelled beyond that place.

Advertising in public spaces

With my mind still swimming with the poignancy of messages posted on memorial benches, and the impact of creative subversion, I jumped onto the Northern Line and was immediately arrested by a Tube card. Set against a bold red background the headline read, “Give to people asking for money. If you have something to spare, please share it.”

At first glance, the hashtag read #SolidarityNotCharity and the logo was the familiar design attributed to Transport for London (TfL).

People asking for money on the tube provokes a whole range of emotions. Being confronted by someone in desperate need within such a confined space is not only difficult to ignore, but can also sometimes be a little intimidating.

Many of us are now rescued from decisions on whether and how much to give because we no longer carry cash. I am always touched by the few people who are still able to produce some coins and choose to give generously to the person begging. But the truth is that most avoid eye contact and seem to hope the embarrassing encounter will pass quickly.

Quite apart from the fact that begging on the tube is illegal, I had always understood that TfL discouraged passengers from giving money directly and instead encouraged donations being made to homeless charities. So, an ad from TfL apparently encouraging people to give money, contrary to that well publicised position, just didn’t ring true.

That’s when I spotted the words sitting underneath the familiar TfL logo; ‘SUBVERTISERS FOR LONDON. PUBLIC SPACE MATTERS.’

This was not in fact a TfL poster as I had first assumed, this was a message posted by creative activists. They didn’t buy the space; they had simply replaced the tube card of the advertiser who had paid for it with their own.

In spite of myself, I couldn’t help admiring the boldness of the message and the placement.

Pursuing the freedom to communicate

Claiming to have learnt their techniques from traditional brand advertising, the Subvertisers seek to use their creativity “to provide an alternative to the powerful and sustained system of propaganda (i.e. advertising) which is destroying the world as we know it”.

Click or tap to play video on YouTube: “Subvertisers for London” (2019)

Describing themselves as “reclaiming public spaces”, they intend to disrupt thinking and communicate messages that run counter to those urging us to consume yet more stuff. I have discovered that the origins date back to 2013, when, a group of French activists acquitted of defacing billboards after arguing their “right of reception” had been violated by being forced to engage with “toxic commercial advertising” in a public space. The judge agreed and deemed that their actions were protected under a freedom of speech defence.

Similar to groups like Led by Donkeys, they hope that their ideas cut through sufficiently to go viral. It worked with me, because here I am writing about it.

It’s the idea that matters most

I can understand why so many people hark back to a supposed “golden age” of advertising at the end of the last century. A time when creativity was king, mass audiences could be reached on traditional media and advertising direct to consumers (now cleverly rebranded as performance media) was the poor relation to broadcast campaigns.

The ultimate prize for advertising was the “big idea”. Something that entwined the brand, message and medium so perfectly that it became part of national discourse and culture. The creativity and craft are easy to admire but what people often fail to talk enough about was how effective that kind of work was. Precisely because it was bigger than the fleeting moment of encounter in whatever medium. It took on a life of its own by occupying our thoughts, conversation, and memories long afterwards and thus ultimately our purchasing decisions.

The irony here is striking. Just as the advertising sector seems to doubt its ability to make that kind of impact anymore, there are creative activists harnessing those very skills to create a counternarrative.

They are seeking to subvert the established system of consumerism by connecting with people once again in public spaces. A well-written poster is the most primary of all communication assets — what could be a more old-fashioned way of reclaiming our streets and journeys?

Perhaps we should look more towards memorial benches for inspiration on how to make far greater impact with our ideas.

At the recent The Future of Media conference, Shay Thompson, the gaming influencer, observed that even 3 billion gamers “eventually want to put down their consoles and be in the real world.”

Public spaces are part of the routine journeys of everyday life. People are always drawn to stories that make them think. We need to be reminded that people are looking for something useful in return for their time and attention. Whether that be new information, advice, a reminder, a request or a deal — but even better if we can make them laugh. That’s what works.

I have now got some cash in my coat pocket ready for the next time someone asks for money.

Jan Gooding is one of the UK’s best-known brand marketers, having worked with Aviva, BT, British Gas, Diageo and Unilever. She is now an executive coach, chair of PAMCo and Given. She writes for The Media Leader each month.

Jan Gooding is one of the UK’s best-known brand marketers, having worked with Aviva, BT, British Gas, Diageo and Unilever. She is now an executive coach, chair of PAMCo and Given. She writes for The Media Leader each month.

Adwanted UK is the trusted delivery partner for three essential services which deliver accountability, standardisation, and audience data for the out-of-home industry.

Playout is Outsmart’s new system to centralise and standardise playout reporting data across all outdoor media owners in the UK.

SPACE is the industry’s comprehensive inventory database delivered through a collaboration between IPAO and Outsmart.

The RouteAPI is a SaaS solution which delivers the ooh industry’s audience data quickly and simply into clients’ systems.

Contact us for more information on SPACE, J-ET, Audiotrack or our data engines.

Jan Gooding is one of the UK’s best-known brand marketers, having worked with Aviva, BT, British Gas, Diageo and Unilever. She is now an executive coach, chair of PAMCo and Given. She writes for

Jan Gooding is one of the UK’s best-known brand marketers, having worked with Aviva, BT, British Gas, Diageo and Unilever. She is now an executive coach, chair of PAMCo and Given. She writes for