TikTok wants us to enter a brave new world. Should we?

Opinion

TikTok is presenting itself not as social media, but as an entertainment company with a focus on community. But is it actually just a form of “soma”?

It takes guts to compare a seven-year-old short-form video sharing app to Shakespeare.

But then no one could accuse TikTok’s top brass of being shy. Stuart Flint, VP of TikTok’s global business solutions for Europe & Israel, argued there is a through-line from the Renaissance playwright to the entertainment produced on TikTok.

“Entertainment has always been with us,” Flint told a crowd at last month’s TikTok For You Summit in Shoreditch, London. “If you think about Shakespeare and the written word, there is a natural connection people just have with entertainment. There’s a need, there’s a passion. Theatre, movies, TV, fast forward to today and entertainment is in our hands, it’s in our mobile phones.”

The statement, which was made to an audience of TikTok influencers and social media marketers, is the latest in a string of diminutives levied against artistic enterprises.

Such rhetoric implicitly reduces all forms of entertainment — even, it appears, Shakespeare — down to equally culturally and artistically valuable “content.”

To quote New York Times staff editor James Bailey, “Martin Scorsese and Logan Paul are not in the same line of work. In practical terms, ‘content creator’ neatly accomplishes two things at once: It lets people who make garbage think they’re making art, and tells people who make art that they’re making garbage.”

That hasn’t stopped media executives like Flint from heightening the value of his own product; he even went so far as to invoke Shakespeare later in his speech by telling the audience TikTok is helping to create the next generation of entertainment.

“It’s a brave new world,” he said. “Jump in.”

Where do I start?

Listening to Flint’s speech as a 25 year-old — a member of TikTok’s prime target audience — I felt completely out of touch. Doubly so after being introduced to one of the Summit’s hosts, Maddie Grace Jepson.

“You may know me from… where do I start?” she said upon taking to the stage.

Well, did I know who Maddie Grace Jepson is? No. Do I know who she is now? Marginally more than I did, I suppose. She is one of the modern-day Shakespeares creating “content” on TikTok.

But the crowd of millennials and fellow Gen Zs cheered loudly for her. When media-industry people talk about fragmentation, this is part of what we mean. A cultural icon for many is a complete unknown to others. Even those that write about advertising and media for a living.

You can see why it can begin to feel cultish.

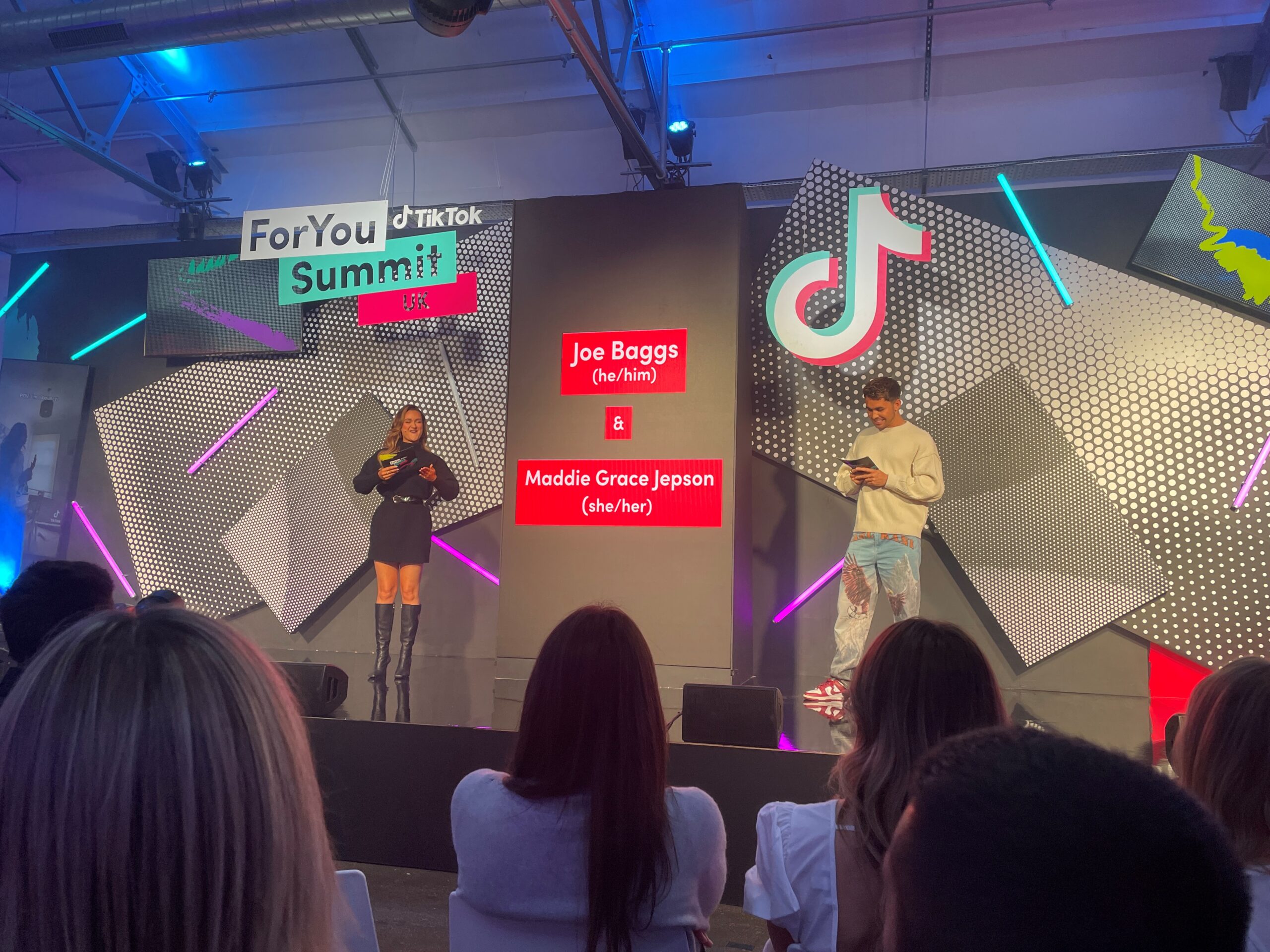

The scene at TikTok’s For You Summit in Shoreditch.

My colleagues and I at The Media Leader have often spoken of our, let’s say, scepticism of social media use. For the sake of transparency, I have never downloaded TikTok on my phone, nor made an account, though I have regularly accessed the site for the purposes of work.

My contemporaries have derided me for my lack of presence on the platform. I am missing out on the cutting edge of culture, they seemed to imply.

Any marketers that feel the same way as I do are also missing out, TikTok executives warned. One after another, they explained how fantastic their product is, and why it’s the best place for brands to be to reach people of all types (but, implicitly, especially valuable young audiences).

Explore who you can be

After Flint espoused how TikTok is more than just social media, cognitive scientist Katherine Templar Lewis took the stage to explain what endorphins are, asking the audience of grown educated adults if they had ever heard of dopamine and oxytocin.

She talked about how entertainment which creates and meets expectations produces positive chemical responses in our brains. As she did so, a drawing on the screens behind her depicted a lab bottle labelled dopamine. The label specified that this particular bottle of the organic chemical was from “Lot 69-420.”

Cool.

Templar Lewis continued to draw on the theme of TikTok as a storytelling medium. Where do we like to consume stories, she asked rhetorically. In communities, of course. It is the sense of community on TikTok, be it through BookTok, CleanTok, TravelTok, or the many other variants of Toks, where people can “explore who they could be.”

The word “community” was uttered dozens of times throughout the evening. TikTok, like many other social media companies, including Reddit and Pinterest, has recently shifted its communication strategy to emphasise its importance. As social media has become less ostensibly social and more advertiser-friendly, fewer individuals actually post much; the ones that do are aiming more for viral success than to simply share images of their personal lives.

So why do people use social media today? Well, beyond mindlessly killing time as we await our inevitable demise, we like to access communities. And, according to Templar Lewis, that’s a positive for users and for brands.

For You Summit hosts Maddie Grace Jepson and Joe Baggs.

Of course, anyone who has ever stepped their digital toe into the internet knows that online communities are also horribly toxic, rage-inducing, and dangerous. But I wouldn’t dare mention that at a TikTok Summit, lest I risk ostracisation.

Joanne Boulos, TikTok’s product marketing lead, tried to head off such concerns. “We want to build the most trusted platform,” she told the crowd. She referenced Project Clover, the company’s effort to physically locate its European data servers in Europe (specifically Ireland), a core component of its attempts to stymie government pressure to ban the app over concerns the Chinese government has accessed and could access user data and influence Western thought.

Boulos asked if anyone had heard of Project Clover. I was one of a scant few in the crowd to raise their hand.

How many goodly creatures are there here

TikTok is a beloved app. Young users spend in excess of 90 minutes per day there on average. That is the equivalent of sitting through half of a performance of Romeo and Juliet.

These users, if the crowd full of them is to be judged by, are unaware or otherwise disinterested in what the company behind their precious platform is doing to keep them safe from undue influence or harm. Instead, they cheer the wonders of snackable entertainment and faux-communities of people they don’t personally know and do not speak to directly.

At this point, as I was looking around and viewing the smiling young faces in the audience, I recalled Flint’s line from Shakespeare earlier: “It’s a brave new world.”

That line originates from a speech given by the young Miranda in Act V, Scene I of The Tempest:

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is. O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.

The irony, which was apparently lost on Flint, is that in the play, Miranda is naïve and blind to the evil that has come for her and her family on their island. Aldous Huxley understood that when he used the phrase as title for his 1932 dystopian novel.

In Brave New World, Huxley describes a world in which citizens are kept peaceful and tranquil through constantly consuming a drug called “soma.”

Presumably, the drug produces lots of dopamine and oxytocin, which in turn makes you care less about personal freedoms because you’re so happy all the time.

What we love will ruin us

In the foreword of his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death, media theorist Neil Postman compared Huxley’s dystopia to George Orwell’s later authoritarian vision of the future in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

“What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy.”

He concluded, “In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.”

Is TikTok our soma? It apparently wants to be.

But if you want to better understand how hate and love can ruin us, read Nineteen Eighty-Four, or Brave New World, or Romeo and Juliet.

That “content” holds actual value.

Jack Benjamin reports on social media and publishing for The Media Leader.

Jack Benjamin reports on social media and publishing for The Media Leader.